The piano has been central to the development of jazz music, but just who are the best jazz pianists of all time? Here are, or what we think are, the greatest jazz pianists ever, but have we ever missed your favourite?The list is in alphabetical order.

- Six of the best: jazz cameos in pop

- Six of the Best… Jazz hit singles

- The 20 Greatest Pianists of all time

- 25 greatest jazz saxophonists of all time

Mose Allison (b.1927)

Singer-composers are not all that common in jazz. Vocalists have usually concentrated on reshaping the riches of the great American songbook or the blues, calling attention to their interpretations rather than the qualities of the original material. Which is all the more reason to praise and prize the distinctive talent of octogenarian Mose Allison who, in a career stretching back beyond five decades, has produced a unique body of work.

Allison’s songs are unmistakeable – wry, bluesy comments on the contemporary scene that manage to be streetwise and satiric, down-home and hip. If they have not made him a household name, they have earned him the devotion of fans all over the world, and the respect and emulation of a couple of generations of his fellow singers, including stars of rock and pop.

undefinedThe tangy variety and range of Allison’s style reflect his origins. Born in rural Mississippi, he absorbed blues and boogie-woogie from an early age, as well as classical piano and the innovations of bop. In 1956 he made the leap to New York, where he found quick employment as a pianist with the likes of Stan Getz. >But he soon began to pursue his real vocation as a jazz minstrel, which he has continued ever since, performing his songs on the international club and festival circuit and making a string of records.

An irresistible cross-section of the results appears on the Warner compilation, Introducing Mose Allison. The introduction begins with the very first track, an Allison hit titled ‘New Parchman’, in which a convict on a Southern prison farm drawls: ‘The place is loaded with rustic charm’. The sardonic sentiment is pure Allison, as is the driving groove, punctuated with jabbing dissonances and whirlwind forays into new keys.

Every track has that kind of wit and energy, aspects of the central impulse that, on one of my favourite pieces, he calls his ‘Swingin’ Machine’ (‘It’s much more felt than seen.’) Always, the Allison muse is fed directly by personal observation, as in the tune he wrote to rebuke noisy audiences: ‘Your mind is on vacation, but your mouth is working overtime.’ There’s plenty to savour here from a true original, survivor and jazz bard.

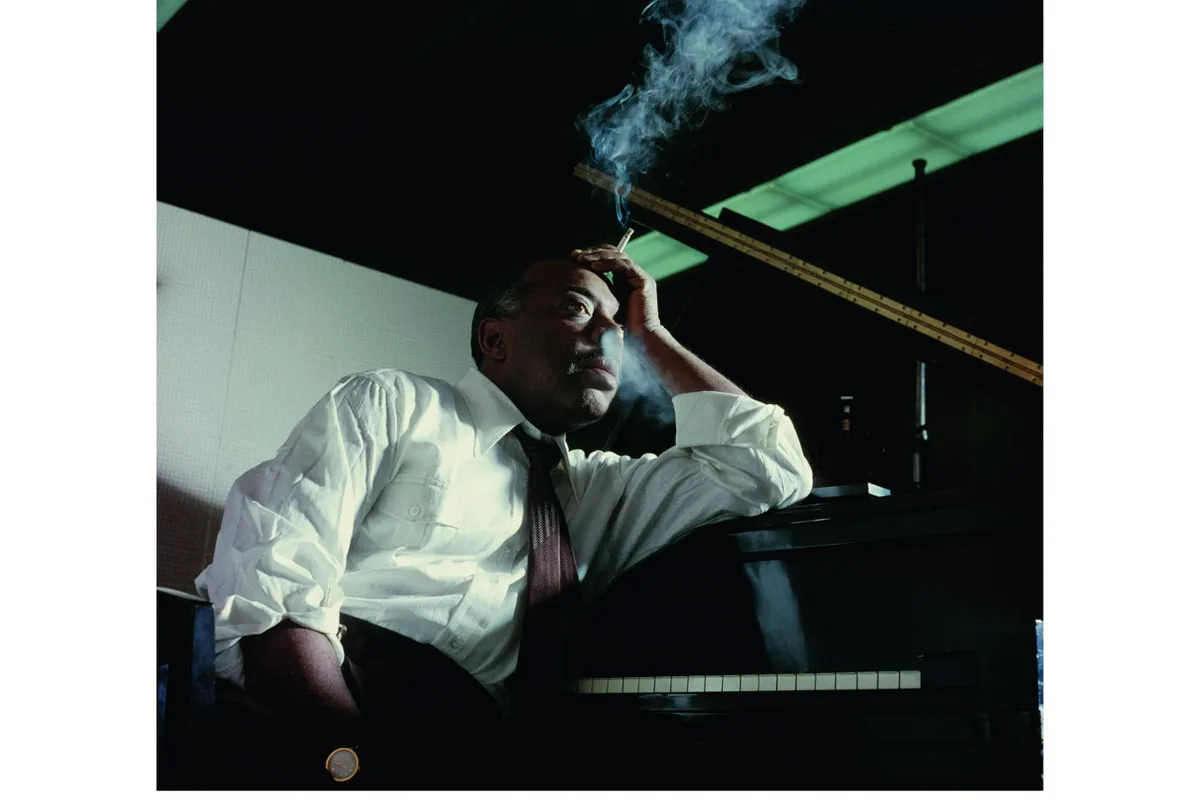

Count Basie (1904-1984)

Count Basie’s name brings to mind associations that might seem contradictory: a famously minimalist piano style and the celebrated big band he led for 50 years. In fact, the two were perfect complements. The Basie band took much of its character from the subtle way the Count’s pithy, elliptical attack framed his shouting brass and saxes. More crucially, Basie’s touch set the tone for the band’s rhythm section; the light, insistent pulse that generated the irresistible current of swing that lifted soloists and ensemble to heights of inspired excitement.

That excitement hit the big time beginning in 1936, when the Basie crew came east from Kansas City (KC). Their success was based on a simple formula of creating in an ensemble the spontaneity and fire of small-group jazz. The key was the band’s line-up of great soloists, including tenor saxophonists Lester Young and Herschel Evans and trumpeters Buck Clayton and Harry Edison. Original tunes, uncomplicated but driving, provided a jumping-off point for solos backed by riffs which seemed a corporate extension of the solos themselves. And underpinning the whole was Basie and his floating, insinuating rhythm. The results can be heard in any number of records, including Basie’s famous ‘One O’Clock Jump’, a string of solo choruses building to a churning climax. But that unique sound depended on the strength of its components. When his stars departed, and the swing era waned, Basie changed tack. While the Basie band of the ’50s boasted first-rate players, it emphasised power, precision and well-crafted arrangements. The Count’s deft piano still produced an infectious rolling swing, but many jazz fans felt this sleek unit was a different creature from the lean, mean cat from KC. But the latter group had some appealing hits, including ‘April in Paris’, with Basie’s ‘one more time’ tag, and the languid arrangement by Neal Hefti, ‘Li’l Darlin’’. Both are present on the Avid two-CD set (left). Each represented ensemble reveals the wonderful things that happened when, in the words of Billie Holiday, ‘Daddy Basie would two-finger it a little’.

Carla Bley (b.1936)

Though Carla Bley was once proclaimed ‘the Queen of the avant-garde’, she’s too much of a free spirit to be defined by a label. Born in California 70 years ago in May, she learned piano from her choirmaster father and accompanied services from an early age, before dropping out of church and school to concentrate on competition roller skating. At 17, jazz seized her attention and she went to New York, waiting on tables at Birdland and absorbing the musical ferment. In 1959 she married pianist Paul Bley, who encouraged her talent for composition, and tuneful originals such as ‘Sing Me Softly of the Blues’ became contemporary standards.

As a performer, she became known in free jazz circles for high energy abstraction. But composing remained closest to her heart, as a means of realising the teeming spectrum of styles that spoke to her. The Beatles, Satie, hardcore rock, Indian ragas, blues and gospel, Latin and free – they all claimed a place in the Bley musical imagination, compounded with a wicked instinct for satire. And in 1971, those multiple tendencies converged in The Escalator over the Hill, a jazz opera which attracted critical acclaim if not many performances. Bley became a fixture on the global post-modern scene, touring with an array of groups from duos to big band, performing new originals and recording on her own WATT label. Her work has continued to evoke a wide range of influences (Bruckner is among her heroes) and her command of the big band genre is witty and ingenious, realised by her regular corps of virtuoso musicians, including her husband, bass guitarist Steve Swallow, and British tenorist Andy Sheppard. One of her recent projects is Looking for America. On sketching melodic ideas she found that fragments of ‘The Star‑Spangled Banner’ kept cropping up. An American liberal troubled by Iraq, Bley was bemused that ‘my new piece had a patriotic virus’, but, typically, stuck with it. What came out is an exhilarating mix of Charles Ives and Charles Mingus, mockery and nobility, bombast and boogaloo – all magnificently played. Though Bley may have gone looking for America, she wound up, as ever, finding herself.

Dave Brubeck (1920-2012)

Dave Brubeck has been incredibly well-known for most of his career. His early success with college audiences – the Brubeck quartet virtually invented the campus circuit – catapulted him on to the cover of Time magazine in 1954. (The pianist’s reaction was embarrassment: he felt Duke Ellington deserved the honour.) In 1960 his star status increased with the album Time Out. Brubeck’s mixture of asymmetrical rhythms and catchy tunes won international renown, though the disc’s biggest hit, the sinuous ‘Take Five’, was written by the quartet’s alto saxophonist Paul Desmond, with some structural advice from his boss.

But, as all too often in jazz, popular celebrity inspired critical condescension. He was slated for his ‘academic’ approach – he had studied with Darius Milhaud – his use of such classical devices as counterpoint and polytonality, his sometimes thunderous keyboard attack and disinclination to swing in a conventional manner. Critics damned his lyricism with faint praise and dismissed him from the jazz tradition. However, over the years, as the idea of a monolithic tradition has become suspect, Brubeck has come to be seen as a remarkable, original talent. Far from being some kind of uptight academic, he still has trouble reading music and is one of the most purely intuitive pianists jazz has produced. His style is founded completely on a commitment to musical expression, fuelled by a belief that, as he once put it, ‘jazz should have the right to take big chances’ – even going beyond what has been considered jazz. And, even though he has just turned 90, Brubeck continues to tour, compose and display his lifelong zest for making music. A handsome survey is contained in The Essential Dave Brubeck, a two-CD set selected by the pianist, ranging from a freewheeling trio in 1949 to the recent quartet. Particularly impressive is his partnership with Paul Desmond, whose wit, swing and invention provided a lucid foil for Brubeck’s experimental ardour. The classic quartet, with Desmond and super- drummer Joe Morello, is well represented, including tracks from Time Out and Time Further Out.

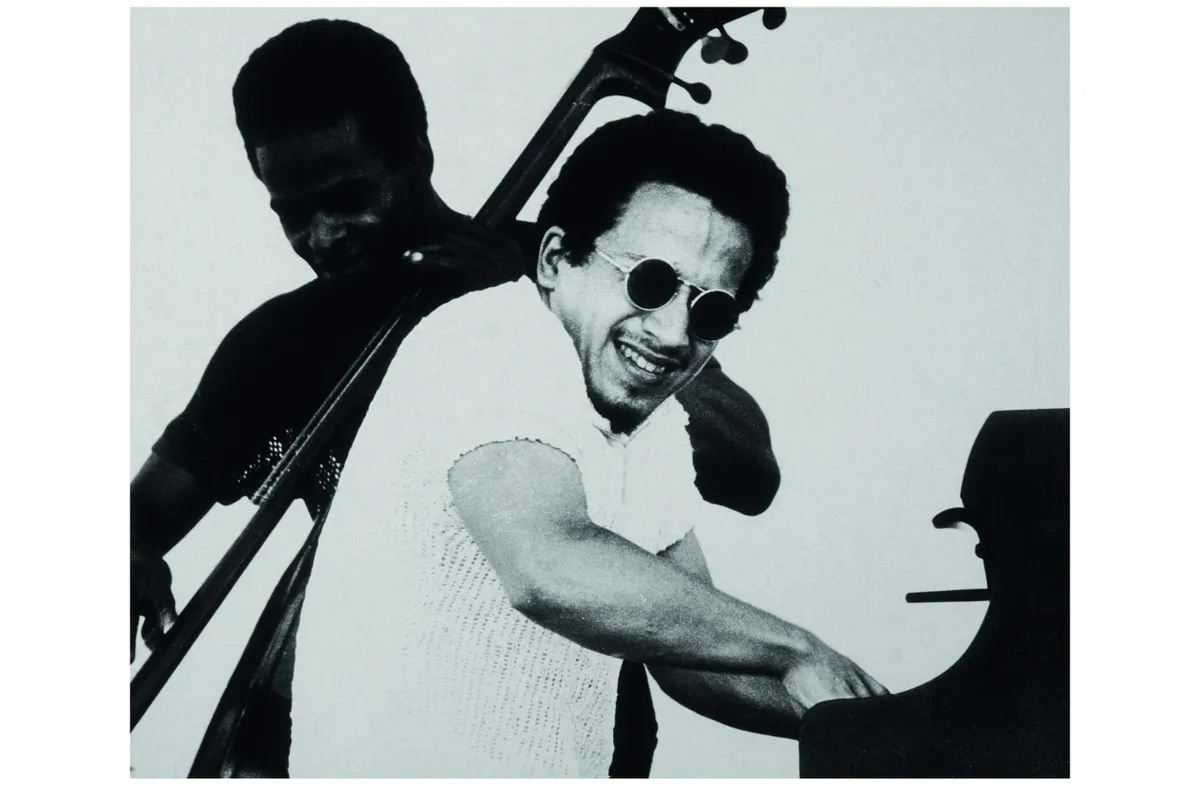

Chick Corea (1941-2021)

Acoustic, electric, latin, free – Chick Corea’s career seems to have touched all the bases in today’s jazz scene. Yet that variety is firmly centred in some abiding principles: a passion for music, the piano and performance. They were a kind of birthright. The son of a professional musician, Corea grew up surrounded by music. Piano lessons instilled his well-grounded technique and love of the classical tradition. At the same time, he got into jazz, particularly the hard bop attack of pianist Horace Silver.

Formal education frustrated him. After a few weeks first at Columbia University, then at Juilliard, where he’d been accepted to major in the piano, he left to commit himself to jazz. Working with all kinds of bands, and absorbing all kinds of styles – with a special fondness for fiery Latin rhythms – Corea built a reputation as composer and player, confirmed in such albums as Now He Sings, Now He Sobs, with bassist Miroslav Vitous and master-drummer Roy Haynes.

In 1968, his career took a leap with a call from Miles Davis. Corea’s tenure with Davis included the epoch-making Bitches Brew, but he found the electronic ambience too fragmented, lacking ‘romance or drama’. He sought those qualities in solo improvisations and with Circle, a free-form trio, then subsequently formed the quintet Return to Forever in 1972. It featured electric instruments, a vocalist and such exuberant originals as ‘La Fiesta’. But he still found drama in acoustic music – scintillating duets with vibes virtuoso Gary Burton and his reconstituted trio with Miroslav Vitous and Roy Haynes.

For the last 20 years Corea has followed his instincts in multiple directions, touring solo, and with ‘Elektric’ and ‘Akoustic’ bands. Corea once said he sought to combine ‘the discipline and beauty of the classical composers with the rhythmic dancing quality of jazz’ – which is an apt description of the recordings in his personal ECM compilation. Ranging from Return to Forever’s joyously lyrical ‘La Fiesta’ to the extraordinary trios with Vitous and Haynes, their impassioned creativity brings to mind the words of William Blake: ‘Energy is eternal delight’.

Blossom Dearie 1926-2009

When Blossom Dearie died the obituaries began by declaring that that really was her given name. It seemed too good to be true, the winsome image so perfectly suited the doll-like delivery which had made her a unique presence on the international scene for over half a century. But that little-girl voice concealed a rare and determined talent. She’d paid her dues in big bands – including a stint with Woody Herman’s singing group The Blue Flames – worked as an accompanist and soloist in clubs, led her own piano trio. Moving to Paris in 1952, she formed a vocal octet, The Blue Stars, who scored an international hit with Blossom’s arrangement of ‘Lullaby of Birdland’ (La légende du pays aux oiseaux). Back in the US, her career flowered, attracting a coterie of fans who relished her distinctive style in jazz clubs and smart cabarets. Dearie’s personal territory was the jazz-cabaret frontier, an adroit blend of delicate swing and wit. As her fellow musicians well knew, she was a collector and connoisseur of good tunes, savouring clever lyrics and chord changes, which she projected with subtlety, insight and humour. But she also loved to swing, and her easy, buoyant sense of time affirmed her jazz credentials. That infectious mix makes the Avid compilation of four albums from the 1950s a delight. It includes her Gallic trip to Birdland with the Blue Stars, while a set with a French rhythm section demonstrates her pianistic side.

But Dearie comes into her own on tracks featuring such elite sidemen as guitarist Herb Ellis, bassist Ray Brown and drummer Jo Jones – classic standards superbly performed, with her sure instinct for vocal nuance complemented by effortlessly perfect grooves. Such aplomb explains the cult following she enjoyed over the years. She was never slow to castigate audiences for rudeness, and some of her best songs have a satiric bite. If you can find it, one of her own favourite discs was the live Blossom Time at Ronnie Scott’s, containing ‘I’m Hip’, a portrait of a jazz pseud. But she herself was the real thing, a jazz musician to the bone. And, despite appearances, no evanescent little flower either, but quietly steely and enduring.

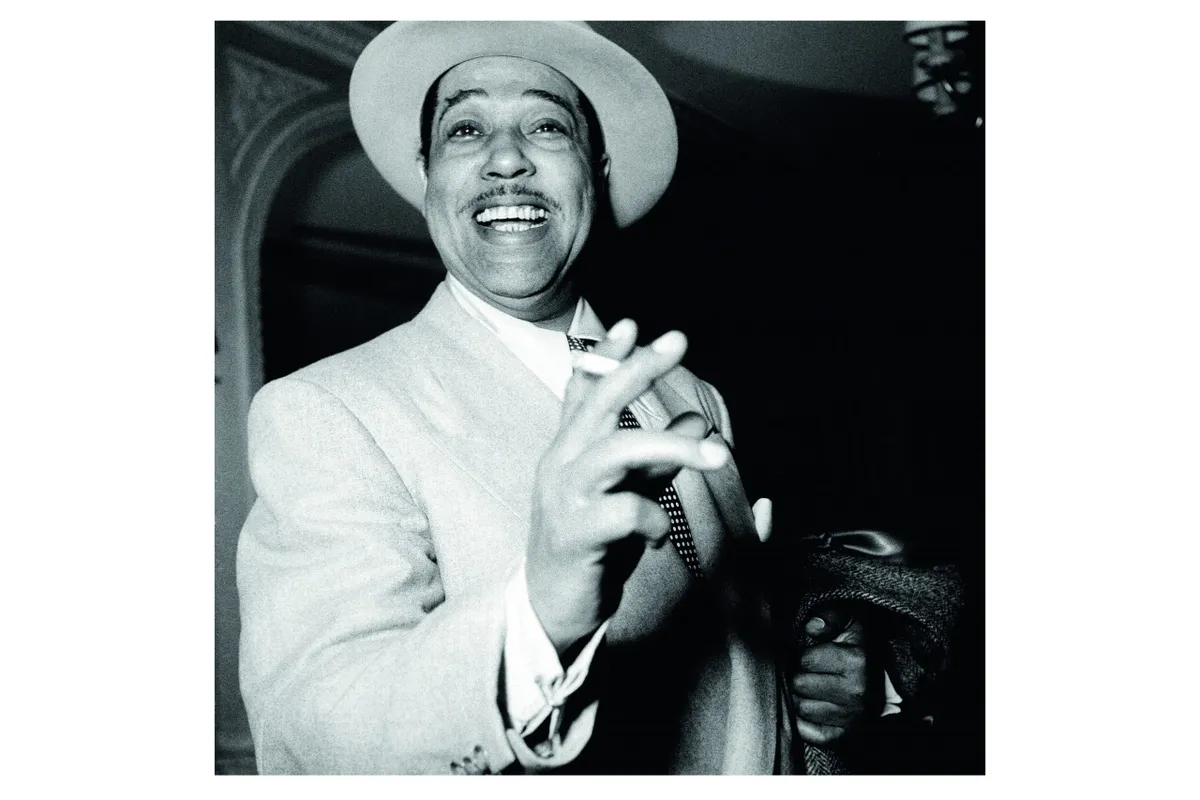

Duke Ellington (1899-1974)

Since jazz is usually celebrated as an improvisor’s art, it may seem paradoxical that one of its major figures was a composer. Though Duke Ellington was a notable pianist, he declared, ‘My band is my instrument,’ and for over half a century he made it the medium of a peerless body of work. For Ellington, composition was never an abstract process, but a direct response to people and situations. He once said, ‘I see something and want to make a tone parallel,’ and the titles of his works are a catalogue of incidents, encounters and atmospheres. ‘Haunted Nights’, ‘The Mooche’, ‘Daybreak Express’, ‘Black, Brown and Beige’ – every Ellington piece enshrines a life in motion, pursued with spontaneity.

And Ellington’s lifelong companions were the members of his band – among them the gutbucket growls of trumpeters Bubber Miley and Cootie Williams, the arching sensuousness of altoist Johnny Hodges and the rumbling majesty of Harry Carney’s baritone. As individual and sometimes contrary a set of virtuosos as ever shared a bandstand, he composed with these sounds and personalities in his head, writing specifically for them. And they provided the raw material for his astonishing originality in harmony and orchestration. To many, Ellington may have been known for such lush popular hits as ‘Sophisticated Lady’, but his colleagues recognised an attainment of another order. As Miles Davis put it, ‘Some day all the jazz musicians should get together in one place and go down on their knees and thank Duke.’

Many critics think Ellington’s finest period was 1940-42, and The Blanton-Webster Band offers a complete chronicle of magnificent music, a sequence of three-minute masterpieces which still dazzle by their variety, daring and sheer creative brilliance. But for a single-disc overview of the ducal experience, try a compilation which was linked to Ken Burns’s BBC documentary from 2000 – Jazz: The Definitive Duke Ellington includes masterpieces from 1927 to 1960, featuring the major Ellington voices and providing a compelling cross-section of an extraordinary accomplishment.

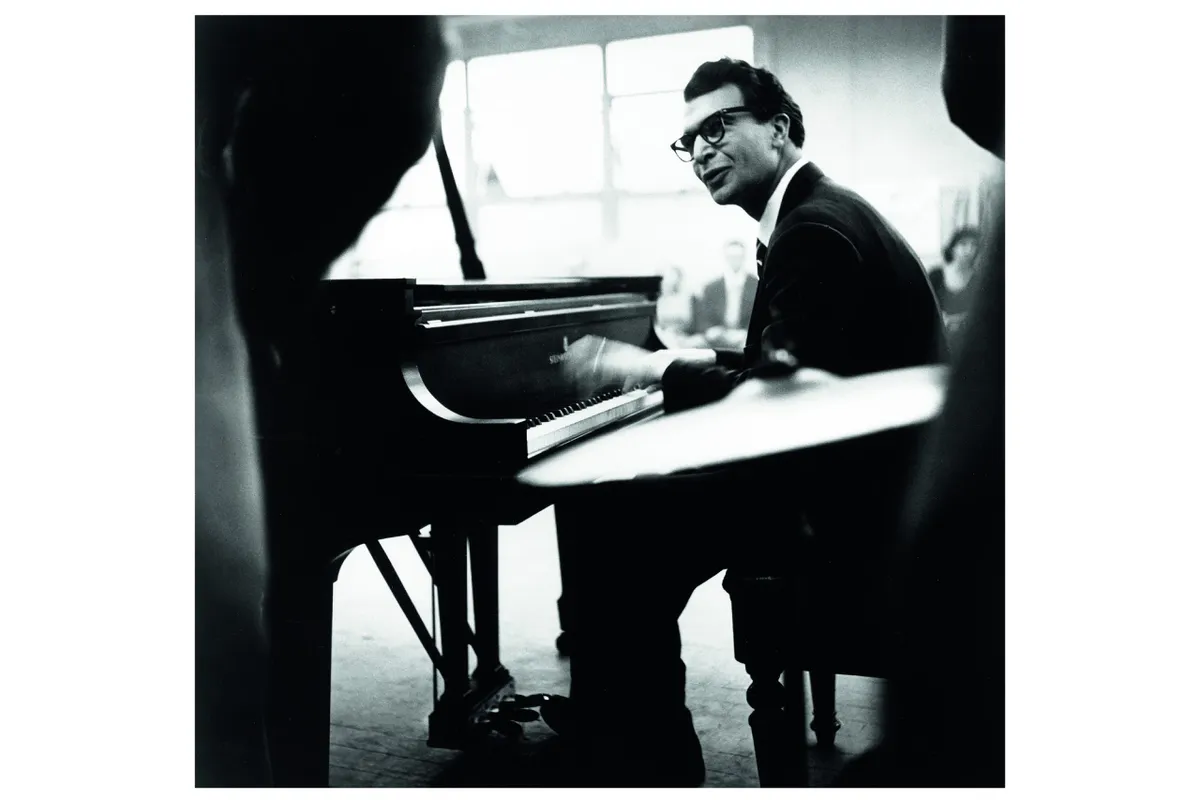

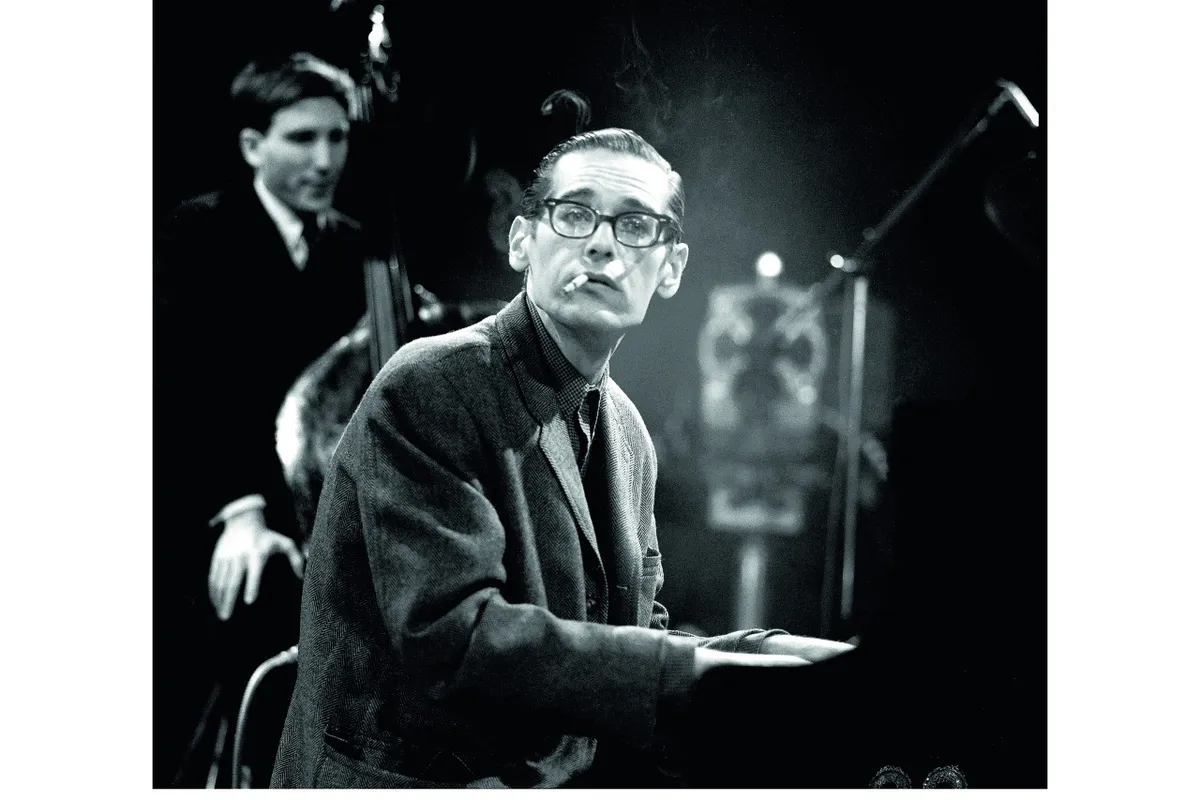

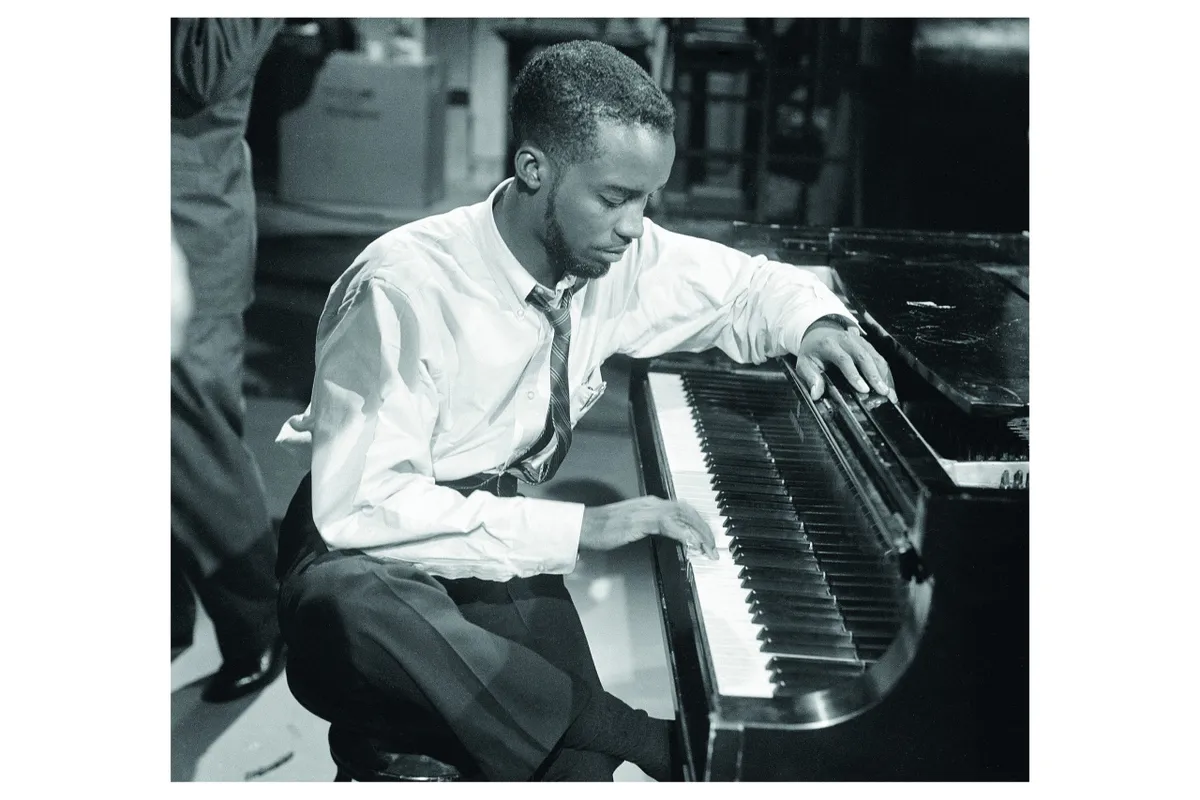

Bill Evans (1929-1980)

In the rakish, outsider’s world of jazz, Bill Evans seemed an anomaly. Bespectacled and unassuming, he had a clerical air which prompted a bandleader to nickname him ‘the minister’. Yet at the piano – head bent over the keys, eyes closed – he was the image of intensity, spinning out the luminous, questing lines Miles Davis likened to ‘quiet fire’. It was his tenure with Davis’s legendary 1958 sextet that made Evans a star, particularly his crucial role in the perennially best-selling album Kind of Blue, recorded the following year. Davis brought the pianist back into the band for this project, knowing his touch would be ideal for its open-ended, modal lyricism. In a series of recordings made mostly with trios, Evans’s unique style won him a celebrity status of his own. His purity of sound, and genius for harmonies and voicings, earned him a reputation as ‘the Chopin of jazz’. Indeed, he knew much of the classical repertoire: he’d performed Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto at college and regularly practised Bach. But his devotion to jazz was primary, as was his conviction that its essence was emotion. Though he took a rigorous view of what he called ‘the extremely severe and unique disciplines’ of jazz, and disparaged wild-eyed abandon, he regarded feeling as the ‘generating force’. That quality of feeling informs the trio recordings he made live at the Village Vanguard in 1961.

Evans’s group marked a revolution in trio-playing: the pianist encouraged virtuoso bassist Scott LaFaro not simply to lay down a beat, but to engage in dialogue. Their subtle interplay, with drummer Paul Motian, illuminates such tunes as Evans’s lilting ‘Waltz for Debby’ and LaFaro’s brooding ‘Jade Visions’. Though some critics found Evans’s art too inward-looking, he could swing too. Everybody Digs Bill Evans is a case in point, with the pianist’s bright, sharp-angled attack supported by the straight-ahead drive of bassist Sam Jones and drummer Philly Joe Jones. Yet the disc also features spellbinding ballads and Evans’s solo classic ‘Peace Piece’. Derived from Chopin’s Op. 57 Berceuse, it’s a mesmerising demonstration of why Bill Evans influenced every jazz pianist who followed him.

Erroll Garner (1921-1977)

Since Erroll Garner left the scene over 30 years ago, in 1977, it’s hard to convey what a phenomenon he really was. Without making any conscious attempt at celebrity, the elfin pianist became that rare thing: a jazz musician who was also a household name. He attracted a huge audience solely by exuberant improvisation, love of good tunes and utterly infectious swing. His talent for giving musical pleasure appeared early. From the age of ten, in his native Pittsburgh, he was a radio star, building a daunting reputation in local jazz circles during the 1930s. When an aspiring pianist named Art Blakey came up against Garner at a jam session, he decided he’d better switch to drums. In 1944, Garner made his move to New York, impressing contemporaries with an originality that, in its wit, drive and virtuosity, harked back to giants such as Fats Waller and Earl Hines. Yet his quick-silver harmonic sense and twisting, questing lines struck a chord with the young lions of bebop. Indeed, some critics dubbed Garner a ‘disciple’ of bop’s chief keyboard luminary, Bud Powell. But at a private piano conclave, Bud hid in the kitchen after Garner played, to avoid following him. Finally, the young pianist sounded like nobody but himself, and assumed top-rank status, performing with the likes of Charlie Parker.

Even more remarkably, he became popular with the mainstream public, winning a devoted following in person, on records and TV. That quality of sheer delight informs every moment of Erroll’s celebrated Concert by the Sea, recorded live in California with a trio in 1955. Here are all the Garner trademarks – the impish, stalking introduction to ‘I Remember April’ which segues into feather-light melody, driven along by the pianist’s pulsating four-to-the-bar left hand; the shifts in dynamics, romantic flourishes, plunging asymmetrical octaves; dancing, blues-inflected lines that sweep forward to a chordal climax. And the hushed, spellbinding ballads that conjure Debussy one minute, Rachmaninov the next. Outside of the music, all we hear is Garner’s occasional guttural rasps and the palpable rapture of the audience which, even today, I’m sure you’ll share.

Read the latest reviews of jazz recordings here

Click here to carry on reading the 28 best ever jazz pianists (2/3)

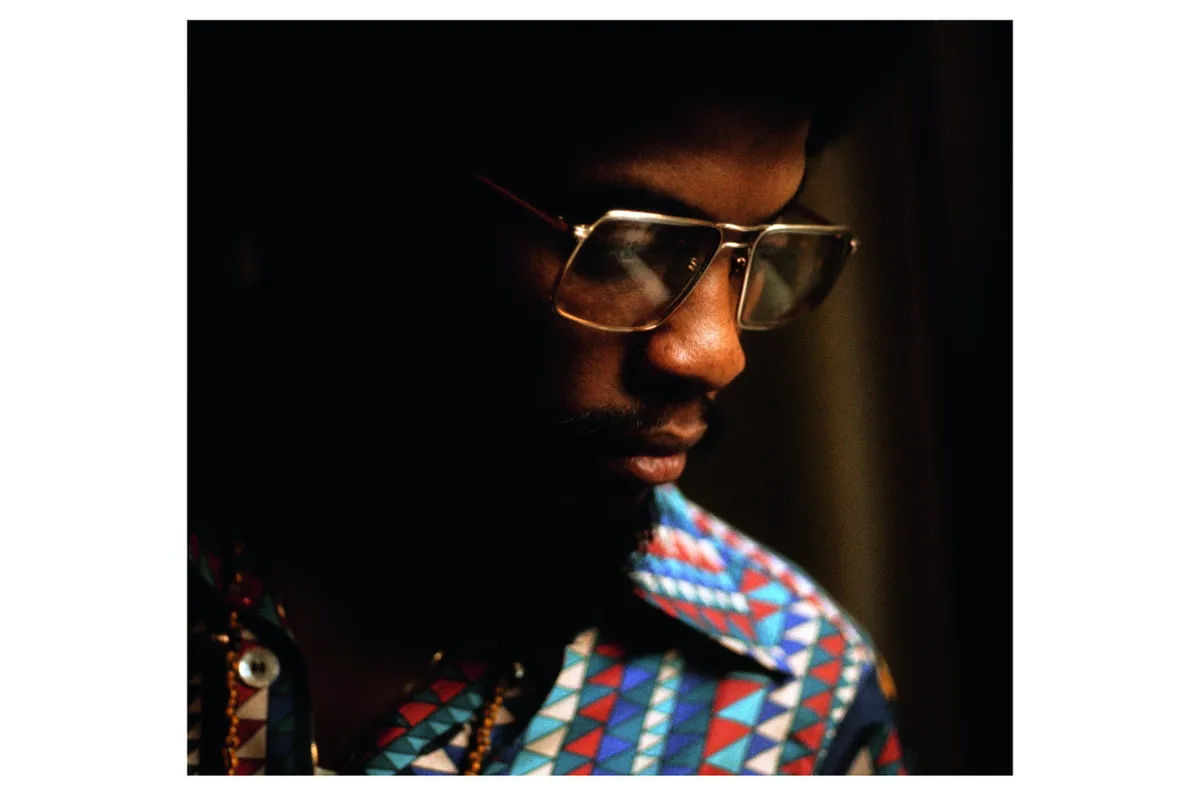

Herbie Hancock (b.1940)

No one better illustrates the polymorphous character of contemporary jazz than Herbie Hancock. Over the last 40 years, as pianist, composer and general creative force, he has deepened the music’s harmonic and rhythmic subtlety, expanded its electronic scope and crossed over to top the pop charts. But his talent has always been restless and omnivorous, from a boyhood appearance with the Chicago Symphony playing a Mozart Concerto to his university days studying both music and engineering.

Although critics debate the relative merits of his achievements, none would dispute the impact of his debut in the early ’60s. His first recording session as a leader produced the soul-jazz classic ‘Watermelon Man’; soon after joining Miles Davis, he began to redefine the function of a rhythm section. Hancock, bassist Ron Carter and the teenage drummer Tony Williams did not hammer the beat into a mechanical groove of tempo plus chord changes, but generated an allusive, intuitive current which opened up all manner of possibilities, with the pianist’s ambiguous, cunningly placed harmonies taking the lead.

In 1965 this dauntingly accomplished trio formed the centre of Hancock’s seminal project, Maiden Voyage. It was a concept album, with five numbers related to the sea, but its most striking feature was the sheer musical richness and variety of each piece. The title tune became a standard almost at once: its quiet pulse mutates between rock, latin and swing, while a long-lined melody evokes some distant horizon and a quasi-modal chord structure, which as Hancock put it, ‘just keeps moving around in a circle’. Hancock later called the work ‘the best composition I ever wrote’, and it inspired his quintet, as did all the material on the session, including another standard-to-be, ‘Dolphin Dance’. The horns comprised the eloquent tenor sax of Hancock’s Miles Davis colleague George Coleman, and the best 1960s trumpeters, Freddie Hubbard.

Throughout this voyage, Hancock is at the helm. He once described jazz as ‘immediate and very adaptable’, and, given this level of authority and invention, capable of momentous artistic results as well.

Fletcher Henderson (1897-1952)

Benny Goodman may have been the ‘King of Swing’, but pianist and bandleader Fletcher Henderson was the power behind the throne.

In the decade before the Goodman band ignited the Swing era in 1935, Henderson defined the way in which the pulsating spontaneity of jazz could be translated into orchestral terms. Many of the key arrangements that propelled Goodman to fame were Henderson originals, which became more celebrated in their secondhand versions than by Henderson’s band.

This may seem another instance of white popularity co-opting black art, but the full story is more complicated. Though a superb musician and peerless judge of talent, Fletcher Henderon was reckoned a hopeless leader. His sidemen described him as relaxed, vague and plain lazy, a reluctant disciplinarian capable of arriving at a gig a month late or early. Curiously passive altogether, he had drifted into music after studying as a chemist, and continued to pursue a haphazard course until his death at 55 in 1952, never reaping the rewards his stature warranted.

That sense of frustrated opportunity becomes all the more intense in the presence of his musical accomplishments. The compilation devoted to him in the Ken Burns Jazz series takes his band from its beginnings to the ’30s, demonstrating both its evolution in style and the astonishing quality of the personnel Henderson recruited. In 1924 he enlisted a young trumpeter he had first heard in New Orleans in 1921: Louis Armstrong’s effect on the band was galvanic, transforming its rather prim East Coast attack with his rampaging Crescent City genius. Central to the ensemble’s impact were the potent arrangements, provided by Henderson, his brother Horace and Don Redman. Fletcher’s own ‘King Porter Stomp’ is an object lesson in big-band writing, in which the swinging interplay of brass and saxes launches the solos and generates a single inspired wave of rhythm from beginning to end. Though this piece became one of Benny Goodman’s greatest hits, his band couldn’t match the irresistible surge of invention created by the Henderson men.

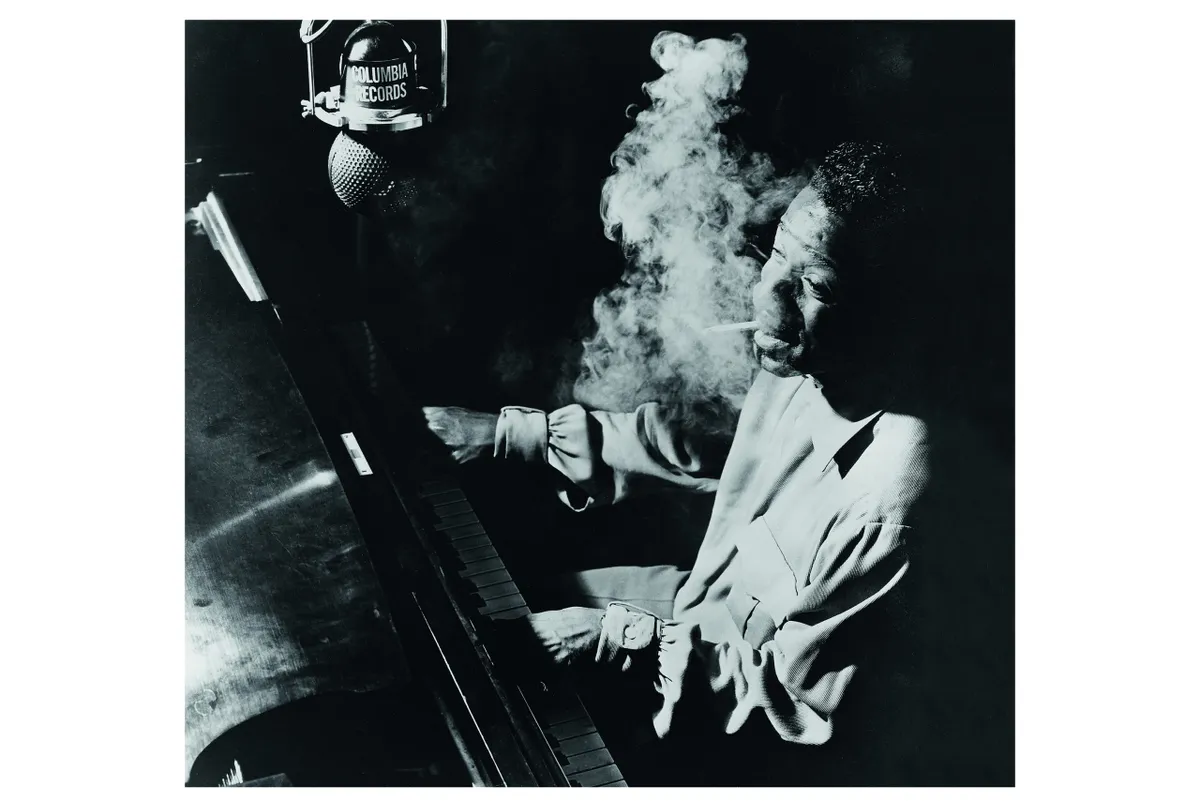

Earl Hines 1903-1983

A few years ago a correspondent to Radio 3’s Jazz Record Requests described Earl Hines as ‘underplayed, largely unavailable and probably underestimated’. It’s a fair summary of a situation that, in the 1930s, would have been unthinkable. Then, Hines was riding high, the king of the keyboard, a byword for invention, technique, daring and dazzlement – the man who turned piano playing into a kind of Olympic event, inspiring a whole generation.

A groundbreaking series of recordings, both solo and with his fellow trailblazer, Louis Armstrong, catapulted him to fame in the ’20s. Through the ’30s and ’40s, Hines led a big band, which, in its latter days, included such bebop pioneers as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. In 1948, he joined forces with Armstrong again, as a member of Louis’s All-Stars, and then in the ’50s he went off on his own. Musical fashion restricted him to the well-trodden paths of Dixieland, and by 1960, he was thinking of retiring. But in 1964, a sensational set of solo concerts in New York put him back on top, where he stayed, playing with authority until his death in 1983, short of his 80th birthday. Naxos’s compilation, The Earl, presents a vintage selection of performances from 1928 to 1941, showcasing his trademarks – the ‘trumpet-style’ right hand, which projected melodies with the bright, attacking power of a lead instrument, cascading, asymmetrical forays which could start and stop anywhere, overturning metre and harmony, and a left hand which seemed to operate independently, launching off-beat chords and chromatic runs. It was exhilarating, as though the oom-pah rhythms of stride and ragtime had gone cubist. Hines loved the sense of drama palpable on ‘Weather Bird’, his duet with Armstrong. As the pianist once put it, ‘I go out in deep water and I always try to get back’. He always did, with every wrong-footing flourish finding its way home. The Naxos disc includes tracks by his big band but I prefer his solo piano magic, which abounds in the set he made in the ’70s devoted to Duke Ellington. A blend of audacity and majesty, exuberance and meditation, it’s a monument to the legacy of Hines.

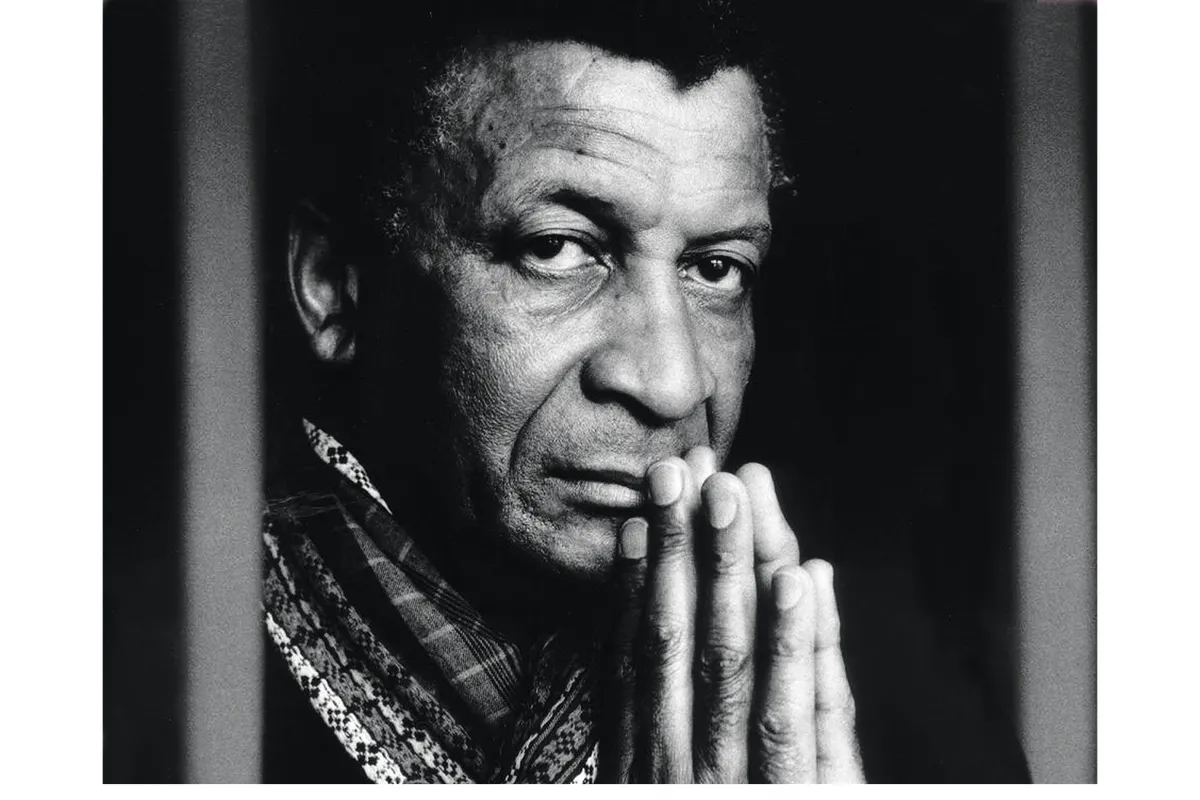

Abdullah Ibrahim (1928-1975)

To the early historians of jazz, the music’s African essence was indisputable. More recent critics, however, have seen the African influence as only one of its aspects, giving equal weight to the heritage of European harmony and form, and stating the true essence of jazz is America’s protean creativity.

Yet Africa has produced its own distinctive jazz culture, epitomised by the pianist-composer Abdullah Ibrahim. Originally known as Dollar Brand, he, too, is an amalgam of influences, absorbing the music of the African Methodist Episcopalian Church in Cape Town from his pianist-grandmother and American standards from local dance bands, as well as, on record, the omnipresent strains of Duke Ellington. That community was steeped both in its own native musical traditions and the oppression of apartheid, where playing jazz amounted to a political act. In 1960, with his groundbreaking sextet the Jazz Epistles, Dollar Brand made South Africa’s first modern jazz album by non-whites, before emigrating to Switzerland. There, his life was changed by an encounter with Duke Ellington, who promoted him. The pianist began to make an international reputation, while staying close to his roots. In 1968 he converted to Islam, becoming Abdullah Ibrahim, and returned to South Africa as often as the tyrannical conditions would allow. In the 1970s he made some robust recordings with his South African colleagues; even when resident in America in the 1980s, he called his band Ekaya: ‘home’. Finally, the collapse of apartheid brought him home indeed, where he played at Nelson Mandela’s 1994 inauguration. In 2004, Ibrahim marked his 70th birthday with A Celebration, a CD surveying his career. Consisting almost entirely of originals, it features him on vocals, bamboo flute and soprano sax as well as piano, with South African sidemen and Americans. Tunes like ‘African Market Place’ and ‘Ancient Cape’ display the throbbing rhythmic ostinatos and infectious melodies that are Ibrahim trademarks. In the disc Voice of Africa the music feels African, charged with a communal joy and faith which still lie at the heart of jazz and reach out instantly to anyone.

Ahmad Jamal (b.1930)

Now in his eighties, Ahmad Jamal can look back on a chequered career. When he formed his first trio in 1951, modern jazz piano was defined by the bebop heroics of Bud Powell – furious lines poured out over a surging beat like a musical roller coaster, following the dips and swoops of a tune’s chord structure to a breathless climax. But Jamal took a different tack, creating space and variety, teasing, shifting grooves that rejected bop’s headlong compulsion. And his keyboard touch was distinctive, airy, playfully melodic, with flashes of virtuosity. Critics were bemused and suspicious, all the more because the Jamal trio attracted a growing public, capped in 1958 by the disc But Not for Me, recorded live at Chicago’s Pershing Lounge. It remained a bestseller for two years, confirming, to large segments of the jazz establishment, that Jamal was just a glorified cocktail pianist. As one writer snidely put it, he might play piano, but his real instrument was the audience. But such jaundiced observers were hard put to explain why the Jamal fanbase included so many musicians, most prominently Miles Davis. He was an unashamed Jamal groupie, declaring, ‘I live until he makes another record.’ What impressed him were the characteristics the critics scorned – the pianist’s feeling for breadth, texture and melody, his escape from bebop orthodoxy, his ability to fashion new structures out of routine forms.

Returning to the hit album At the Pershing now reveals what the jazz scribes missed. Freed from the taste of the age, its virtues are remarkable. Jamal has rethought the whole trio format, so that each piece becomes a fresh experience, defying prefabrication. All three players are equal: he accompanies the bass and drums as much as they do him. Melodies are transformed by subtle vamps and interludes, making a tune swing all the more. And the group swings like mad: their classic ‘Poinciana’ is a distilled New Orleans street parade with a latin touch, as Jamal muses over Vernell Fournier’s insinuating beat. The disc’s abiding pleasure confirms the pianist’s motto that ‘there’s no such thing as old music’. He himself is still in his prime.

Keith Jarrett (b.1945)

Depending on your view, Keith Jarrett’s status is either problematic or exalted. Is he a pianist whose gifts are compromised by grandiose flights of whimsy or, as a critic put it, one who ‘uniquely connects to a type of universal/musical consciousness’? For Jarrett, jazz is not a tradition or a vocabulary, but a spiritual process that involves opening yourself to true creativity; ‘an attempt,’ he said once, ‘over and over again, to reveal the heart of things.’ When I first encountered him at a Stan Kenton music camp in 1961, he was a bright 16 year-old who could play brilliantly in any style, jazz or classical, not to mention his own. No surprise that he became a star with the Charles Lloyd Quartet, from 1967-70, whose flower-power ethos suited him perfectly. Subsequently, he led his own groups, but it was with his solo concerts from 1972 that he reached cult celebrity. Jarrett’s free-form improvisations would start with no prior theme or direction and cover all manner of idioms, from gospel vamps to Romantic rhapsodies, propelled for up to an hour by an intense lyricism. Just as intense was his manner – flailing, moaning and gasping. The heady atmosphere came through on record: his 1975 Köln Concert sold over a million.

Solo improvisation continued to be central to Jarrett’s work. Besides piano, he’s recorded on clavichord, pipe organ and soprano sax, plus – on the home-made multi-tracked project Spirits – ethnic flutes and percussion. Revealingly, such tracks comprise the bulk of the material he selected for his 2-CD retrospective in ECM’s :rarum series. But there are also examples of his ensemble partnerships with saxophonist Jan Garbarek, and the Standards trio, which Jarrett formed in 1983 with his fellow virtuosos, bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Jack DeJohnette.

The Standards trio has become the pianist’s regular touring group, exploring tunes from the treasure trove of American popular songs and classic jazz themes as well as originals. On albums such as Up for It, the results are sublime: focused and intelligent, spontaneous and inspired, joyful and swinging. Whether you accept all Jarrett’s views on jazz, this music is the real thing.

Brad Mehldau (b.1970)

Though the jazz wars rumble on, jazz itself seems to be thriving. Younger players learn from the masters of the past without worrying about being labelled ‘retro’, and recognise that experimentation need not mean ear-numbing violence or funny-hats whimsy. A perfect example of someone recasting the jazz tradition in a wholly contemporary personal style is Brad Mehldau, widely regarded, now in his forties, as the leading jazz pianist of his generation. Steeped in classical keyboard lessons as a child, he switched to jazz in his teens, studying and performing in New York. In l994, after making a reputation as a sideman, he formed the trio which has been his principal medium ever since.

It’s typical of Mehldau that he doesn’t view the conventional trio format as any inhibitor to creativity. He glories in its possibilities: he and his regular partners, bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jorge Rossy, have recorded a sequence of five albums titled The Art of the Trio, a kind of object lesson in how much invention the standard line-up can generate. Mehldau’s secret is his constant originality. Even familiar material sparkles with new life in the trio’s interpretations, with no sense of a jazz group merely running through its jazzy paces.

The pianist’s solos are marvels of sustained, deeply felt discovery: his mastery of classical technique provides him with a wide expressive palette and each note is part of an evolving narrative, with its own considered weight and colour, whether shaping oddly tilted, asymmetrical phrases or silvery runs. His taste for varied harmonies and dynamics is complemented by Grenadier and Rossy, and their absorbing interplay constantly suggests new directions, carried along by a subtly pulsing rhythmic drive. A superb example of the trio’s artistry – and their wide-ranging repertoire – is their most recent CD, the highly praised Anything Goes, incorporating standards by Cole Porter and Thelonious Monk, tunes by pop stars Paul Simon and Radiohead, and winding up with a remarkable bitonal version of ‘I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face’, epitomising the blend of irony and romance which is Brad Mehldau’s special territory.

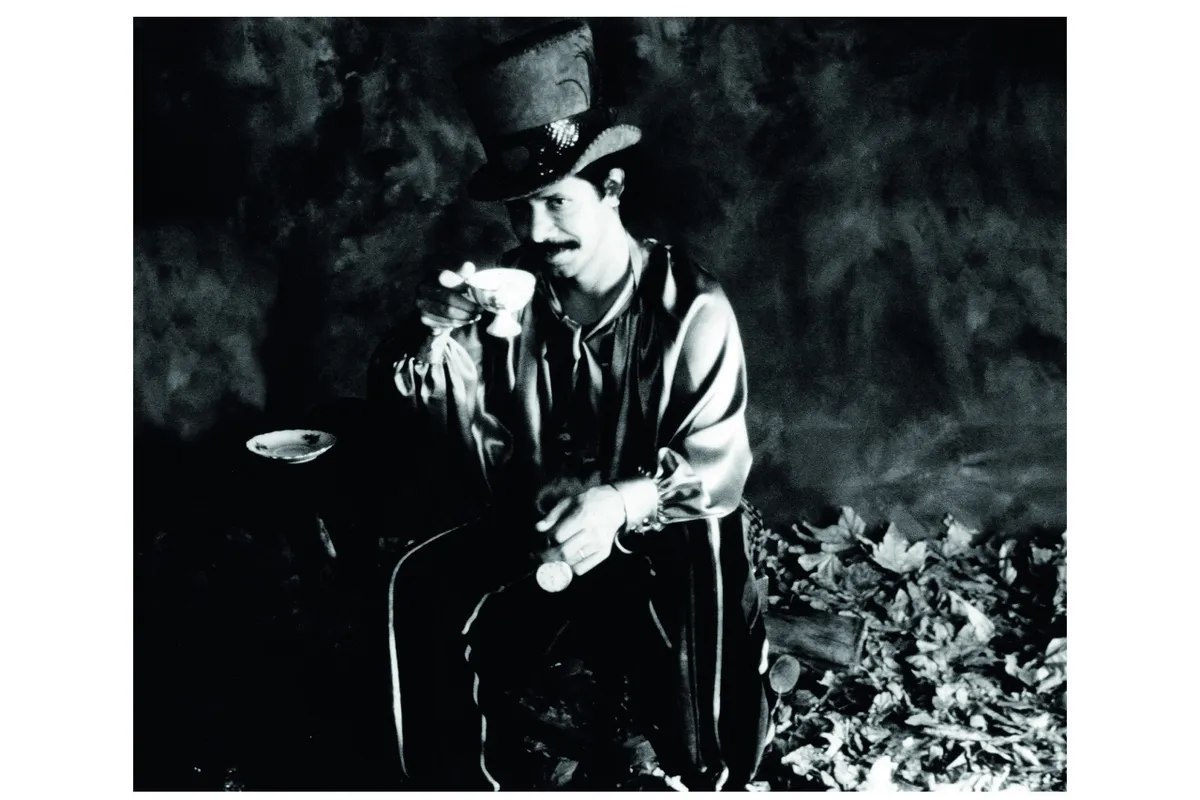

Thelonious Monk (1917-1982)

Even people who don’t know much about jazz are aware that jazz musicians are meant to be ‘characters’ – free-spirited types whose absorption in music generates bizarre behaviour. Though this hipster mythology is exaggerated, it seemed made for Thelonious Monk. His mystique was compounded by his unforgettable name (albeit the same as his father’s), his taste for exotic headgear, a penchant for breaking into impromptu dances on the bandstand and a jabbing, idiosyncratic piano style punctuated by the silences which also marked his everyday demeanour. But Monk’s media status as the ‘high priest of bebop’ obscured the real nature of his achievement.

At a time when modern jazz was dominated by harmonic legerdemain and omnivorous technique, he showed that a deep-rooted personal vision was still possible. Monk’s compositions were unlike anyone else’s, full of curiously stretched and sharply angled chords, wrong-footing rhythms, melodies that could be gnomic, rich or grainily lyrical. He defied facility. When you played Monk, you played him on his terms, and his best interpreter was probably himself. His approach to the piano could seem splayed and halting – one fleet-fingered rival dismissed him as ‘hamstrung’ – but he could produce marvellous, probing colours, somehow getting in between the keys to make the piano seem the ultimate blues instrument. And he swung enormously, with spikey accents and clangorous, tumbling runs. As a soloist or accompanist, his timing was perfect, and he could galvanise a rhythm section by knowing exactly when and when not to play. Listening to Monk can easily become a lifelong habit, since what he has to offer is unavailable anywhere else. Perhaps the best place to start is with the Blue Note compilation Thelonious Monk – Finest in Jazz, a collection of classics (‘Round Midnight’, ‘Misterioso’, ‘Straight No Chaser’) imbued with his quirky magic. By now the cult of his supposed eccentricity has waned. Like all the best jazz, Monk’s music is a permanent presence.

Jelly Roll Morton (1890-1941)

As a matter of right, Jelly Roll Morton would have assumed that any jazz starter collection would begin with him. After all, he once proudly proclaimed, ‘I myself invented jazz in the year of 1902’. Grandiosity was his lifelong style: pianist, composer, leader; pool-shark, pimp and hustler – there was something mythic about Jelly, right down – or up – to the glittering diamond in one of his front teeth. People resented his arrogance, but as one of his musicians put it, ‘Sure he bragged, but he could back up everything he said.’ And while he may not have invented jazz, he was arguably the first great jazz composer, the man who proved it was possible to realise both a compelling structure and spontaneous excitement.

The key to his achievement was a many-sided and acute musical imagination, steeped in the cultural melting pot of New Orleans. Morton absorbed all the riches the Crescent City had to offer – blues, ragtime, marches, grand opera, quadrilles and the ‘Spanish tinge’ he maintained was essential to jazz. His piano style displays all these influences, at once refined and raffish, encompassing elegant turns and trills, barrelhouse chords and a strain of melancholy lyricism. The same qualities suffuse his orchestral works. Morton first formed the band he called Red Hot Peppers in Chicago in 1926, and their recordings will come as a revelation to anyone who thinks of early jazz as raucous and one-dimensional. Morton’s men were all masters of the vibrant New Orleans style, and gave his compositions just the right interpretative and improvisatory gusto. The pieces themselves are at once joyful and subtle, strutting and sonorous, demonstrating Morton’s instinct for structure, detail, colour and dynamics. ‘Black Bottom Stomp’ or ‘Grandpa’s Spells’ provide textbook examples of a superbly crafted sequence of instrumental effects and combinations, building to an exuberant climax. The whole of Morton’s recorded output from 1926 to 1930 is available on a five-CD set from JSP. In it, Jelly stakes his claim not only to be ‘Dr Jazz’ (as he crows on one of his most famous discs), but the creator of a unique corner of 20th-century music.

Read the latest reviews of jazz recordings here

Click here to carry on reading the 28 best ever jazz pianists (3/3)

Oscar Peterson (1925-2007)

When Oscar Peterson died, he received the kind of multi-column obituaries that are usually reserved for star entertainers, not jazz musicians. But he was a special sort of jazzman, a pianistic phenomenon who spent his long career bestriding mainstream culture, equally at home in a club as the Albert Hall.

The most obvious key to his renown was his amazing technique, an awesome facility rare in jazz, but which Peterson simply regarded as a measure of sincerity. As he once put it, ‘the whole idea of jazz is that if you think of a phrase, you should be able to play it’. He had no patience with half-articulated fumbling, and his racing mind was matched by his flying fingers. Classical lessons began early in his native Montreal, with a teacher who had studied with a pupil of Liszt, to whom he saw a resemblance in the young Peterson. In 1949, at the age of 24, Peterson made a sensational US debut, bringing the house down at a Jazz at the Philharmonic concert (JATP) in New York. The JATP’s founder, Norman Granz, became his mentor, and the star’s career took off, accompanying a host of jazz legends and leading his own groups. He expanded his partnership with the bassist Ray Brown to create two trios, the first with guitarist Herb Ellis, who was replaced in 1958 by drummer Ed Thigpen.

But the pianist did have his detractors, who resented his accomplishment: for some, his cascades of notes seemed superficial, compared to the craggy directness of, say, Thelonious Monk. But his accomplishment was real, an authentic expression of his love of jazz and performance. He was a great communicator, and his sense of joy as well as his gifts earned him an audience of millions, and the respect and admiration of his peers.

Though bad health – including a stroke in 1993 – slowed him down, he continued to delight his fans until close to his death, aged 83. And there is plenty of delight in such recordings as Night Train, a 1960s array of blues and standards. As Peterson shakes the piano with a chorus of thundering, double-fisted tremolos, you may think, ‘well yes, this might just be the way Liszt would play jazz’

Michel Petrucciani (1962-1999)

A photograph of Michel Petrucciani in the New Grove Dictionary of Jazz shows him being carried by saxophonist Charles Lloyd. In fact, musicians on the festival circuit vied for the honour of bearing the pianist on to the stage. The congenital illness – osteogenesis imperfecta, or ‘brittle bones’ – which stunted his growth and limited his movement made his talent all the more remarkable, and Petrucciani himself an object of wonder and admiration to players and listeners worldwide. His personality was as unique as his ability. Born into a Franco-Italian family of musicians, at four he announced he wanted to play the piano, after seeing Duke Ellington on TV. Fobbed off with a toy instrument, the toddler smashed it, and a proper, if decrepit, piano appeared, adapted so he could reach the pedals.

Classical training followed, but jazz was his ruling passion. Making his professional debut at 13, he quickly came to international attention. Any hint of scepticism at his unprepossessing appearance vanished the instant he sat down and played, and a wave of top-flight support took him from Paris to New York and beyond. His globetrotting career continued until 1999 when he died from pneumonia at just 36. At no point did he trade on his disability. Music was all that mattered, and he pursued it with panache. A testament to Petrucciani’s charisma is the complete recording of his final concert in a triumphant 1997 solo tour of Germany. Comprising originals and standards, it demonstrates the range of his inspiration and technique. Playing without a pause, he conjures sequences that celebrate all the possibilities of jazz piano – from the Romantic harmonies of Ellington and the Impressionism of Bill Evans, to the rhapsodies of Keith Jarrett, the razor-edge bop of Bud Powell, Erroll Garner’s sheer delight. But the spell Petrucciani casts is all his own, as is his remarkable relation to his audience. They are palpably enchanted, hanging on every note, and his witty asides to them create a warmth and immediacy rare in jazz. Petrucciani obviously loved performing, and the occasion celebrates a giant of commitment, passion and joy.

Bud Powell (1924-1966)

All too often, the begetters of bebop confirmed Scott Fitzgerald’s dictum that there are no second acts in American lives. Many, such as Charlie Parker, died young, burned out by the music’s drug-ridden lifestyle. But the fate of Bud Powell, who had as revolutionary an impact on the piano as Parker did on the saxophone, may be more poignant.

A shy, reclusive personality, Powell’s career was blighted by a police beating, periods in mental institutions, alcoholism and TB. During his last decade, his playing veered between flickers of brilliance and painful, fumbling approximation, until his death in 1966 aged 41. There wasn’t a single jazz pianist who didn’t bear the imprint of his fiery creativity. He set both the terms for the modern keyboard style and, in his heyday, an almost terrifying standard of performance.

A Powell piano solo wasn’t so much played as unleashed, its momentum combining dazzling imagination and uncanny technical lucidity. His up-tempo feats were astonishing, as his right hand sent lines spinning over the keyboard, with riffs and bursts of melody punctuated by his left. That non-stop linear virtuosity became the hallmark of bebop piano, but what made him unique was his variety of accent and nuance. This was no mechanical stream of quavers, but a torrent of ideas – accompanied by the pianist’s groans, as if reflecting the intensity of his inspiration. And his ballads were no less highly charged, if more lush and rhapsodic, conveying a trance-like immersion in his instrument. All those qualities illuminate Tempus Fugue-It, a Properbox chockful of vintage Powell. Even early on he is centre of attention, and his later work with Charlie Parker and Sonny Rollins does justice to his gifts. His invention is exemplified in two takes of ‘Fine and Dandy’ made within minutes of each other, pairing Powell and tenor saxist Sonny Stitt. Unfazed by the lightning tempo, Powell comes up with equally amazing solos each time.

His trio performances are more remarkable, turning hoary standards like ‘Indiana’ into blazing revelations. Such achievements are what Bill Evans, one of his heirs, had in mind when he declared that Powell’s ‘insight and talent were unmatched in hard-core, true jazz’.

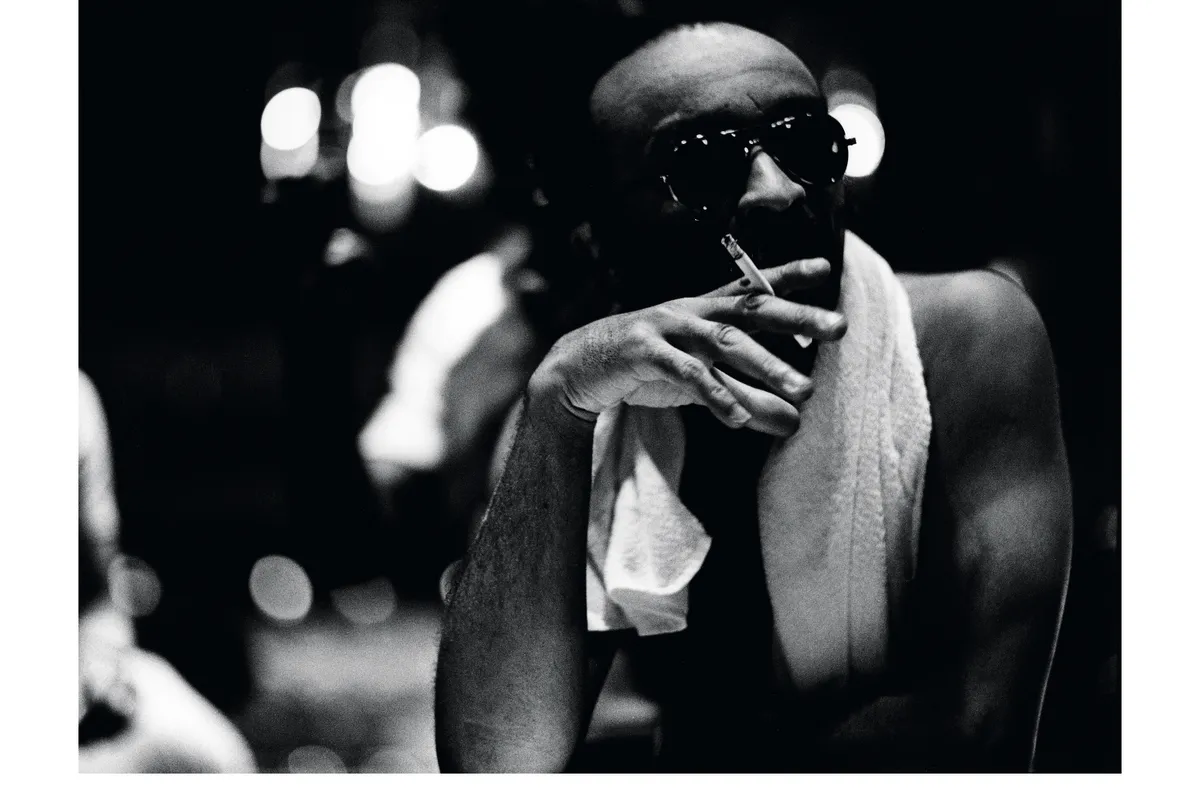

Sun Ra (1914-1993)

In jazz, individuality is part of the job description, but Sun Ra took it to a whole new level. Another dimension, in fact, since the pianist-composer-prophet claimed not to have been born on Earth at all, but to have ‘arrived’ from Saturn, teleported by ‘the Master-Creator of the universe’ to save the world from chaos through his music.

Not surprisingly, many critics refused to take this seriously, but for over 40 years, Sun Ra attracted a cult following with his ‘Arkestra’, a communal band of varying size committed to disseminating his message. And while he and they never got rich, they created a huge body of work that cast a weirdly wonderful spell, pushed forward the frontiers of jazz and swung like mad.

Despite his cosmic claims, Sun Ra was born plain Herman Blount in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1914, to an African-American family of modest means. He quickly displayed remarkable musical and intellectual gifts, and by the age of 20 he was leading his own band. Not long after, he had a vision of his extraterrestrial origins, later compounded with a fascination for ancient Egypt as the source of Afro-European culture. In 1952, he proclaimed his true roots by changing his name to Le Sony’r Ra and formed his own Space Trio, the core of his first Arkestra. Musicians were drawn to him by his charisma, at once down home and far out, stretching their minds and talents. An Arkestra gig was meant to be a brilliant extravaganza, bringing together music, poetry, theatre and dance. Garbed in gorgeous robes, spangled headdresses, masks and gaudy plumage, the band delivered Ra compositions that celebrated space and time, peace and hope, and joyous energy. Over the years, until his death in 1993, Sun Ra pioneered techniques from electronics to collective improvisation. At the same time, blues and swing are never far away, as you can hear on his most accessible album, Jazz in Silhouette. Recorded in 1958, it includes mystic visions, subtle lines and colours, non-stop grooves and exhilarating solos. And we share the whole experience, since, in Sun Ra’s words, ‘You’re all just instruments, in this vast Arkestra called life’.

Esbjörn Svensson (1964-2008)

An EST concert was a piano trio gig unlike any other. Led by the late Esbjörn Svensson, with bassist Dan Berglund and drummer Magnus Öström, the group mesmerised clubs and concert venues not just with their playing, but with spacey effects – electronics, light-shows, smoke – usually associated with stadium rock. And their music had the same kind of manifold appeal – rooted in jazz, but incorporating catchy hooks, grooves and textures.

To Svensson it was all part of reaching out to as wide an audience as possible, which is why his accidental death, in 2008 at just 44, was such a shock. Svensson grew up in small-town Sweden, absorbing classical music from his pianist-mother, jazz from his father and rock and pop from the heady culture of the 1960s and 1970s. The inspiration of Thelonious Monk, Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea framed his pianistic horizon, and he obtained a classical grounding at the Stockholm Conservatoire. Following graduation, studio work and a spell playing bebop, Svensson began the EST (Esbjörn Svensson Trio) project with Öström and Berglund in 1993. After competent early records, something new came in 1996 with a quirky disc of Monk tunes. In 2000, the CD Good Morning Susie Soho made them stars, in both pop and jazz charts. EST were headliners in Europe, Asia and the US. Good Morning Susie Soho is still a good place to start appreciating their energy, invention and quality sans frontières.

The tracks encompass the witty, rock-style clatter of the title tune, Svensson’s Chopinesque musings on ‘Serenity’, razor-sharp free-bop in ‘Providence’ and the tabla-raga mood of ‘The Face of Love’. You can already feel his interest in dramatic shape, his concern that each piece should tell a story. Indeed, for some critics, the group’s commitment to drama undermined its sense of discovery. To them, EST performances seemed less about jazz’s ‘sound of surprise’ than pop’s super-emotional manipulation. But Svensson declared that simply playing jazz was secondary to creating ‘the EST sound… We just try to go to the heart’. That musical heart throbs away on the group’s last double-CD Live in Hamburg.

Art Tatum (1909-1956)

There was something almost mythic about Art Tatum from the beginning. Pianists hearing his first solo recordings in 1933 assumed there had to be more than one person playing: such terrifying virtuosity could not come from a single pair of hands. And yet the amiable prodigy from Ohio – virtually blind from birth – soon became a familiar if still incredible presence on New York’s scene and beyond. Though his style was based on the high-powered facility of such stride masters as Fats Waller, Tatum took their keyboard feats to another level, not just in digital dexterity but in a harmonic and rhythmic command which produced spontaneous transformations of standard tunes. Dazzling sequences of new chords and keys defied the bar lines before returning, with nonchalant precision, to the original structure. Tatum’s mastery was universally acknowledged. When he entered a club where Fats Waller was playing Waller announced, ‘I play piano, but God is in the house tonight.’ And his reputation extended beyond jazz: experiencing Tatum in a 52nd Street club, Vladimir Horowitz exclaimed, ‘I don’t believe my eyes and ears.’ Tatum was essentially a jazz musician, relishing musical immediacy. He loved to hang out in after-hours clubs, seeming to take delight in coaxing wonders out of clapped-out pianos, transcending their stuck keys and dodgy tuning till they glittered like concert grands.

Toward the end of his life – which came prematurely in 1956 at the age of 47 – he was recorded at length in scrupulous studio conditions. But a pair of happy sessions from the same period occurred at the home of a Hollywood music director and Tatum devotee. Issued as a two-CD set on Verve, the occasions were an informal homage. The sound is good and the atmosphere makes up for the few blemishes inevitable in live recording. One gem succeeds another: the likes of ‘Tenderly’, ‘Too Marvellous for Words’, and ‘Body and Soul’ shine with the pianist’s brilliance. They leave you awestruck, shaking your head and inclined to agree with the critic who declared, ‘Ask ten pianists to name the greatest jazz pianist ever and eight will tell you Art Tatum. The other two are wrong.’

Cecil Taylor (1929- 2018)

It might seem odd to include an entry for a musician whom a fair number of critics don’t consider a jazz musician at all. But in a way, that’s jazz – a question-begging activity, defying easy categories with the force of its energy and excitement. And even listeners who dispute Cecil Taylor’s jazz credentials wouldn’t deny his creative intensity. They’d just protest that his furious, free-form piano improvisations, pummelling the keyboard with fingers, fists and forearms, bearing no relation to metre or melody and often lasting well over an hour, belong to the European avant-garde, not African-American tradition. But Taylor himself has always disagreed. Though conservatory-trained and possessing a virtuoso technique, he regards jazz as black music, his way, he once said, ‘of holding on to Negro culture’. His fascination with the rhythmic and harmonic abstractions of Stravinsky and Bartók, Dave Brubeck and Lennie Tristano gave way to the potency of African-American pianists: Ellington, Monk, Horace Silver. Revelling in what he called ‘the physicality, the filth, the movement in the attack’, the young Taylor made it his own. He viewed the piano as percussive – ‘88 tuned drums’, his style an amalgam he dubbed ‘rhythm-sound-energy’.

His ultimate inspiration was the very force of nature: ‘music is as close as I can become to a mountain, tree or river’. Though that kind of mysticism may seem a long way from blues and swing, Taylor’s work has its own intoxication. And in his debut album, Jazz Advance, from 1956, blues and swing are still manifest – his trio and quartet, with soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy, tackle a programme by Taylor himself, Monk, Ellington, even Cole Porter. But Taylor’s approach is already breathtakingly unique. Every tune becomes a Taylor original, recreated by the pianist’s knack for generating new shapes, solos which follow their own motivic logic, oblique, asymmetrical, framed by rhythmic precision and the clarity of his touch. His coherence is not about spinning out licks or getting in a groove. He hollows out his own musical dimension, startling and exhilarating. Jazz Advance is an ideal introduction, a prelude to the torrential flights which have made Taylor legendary.

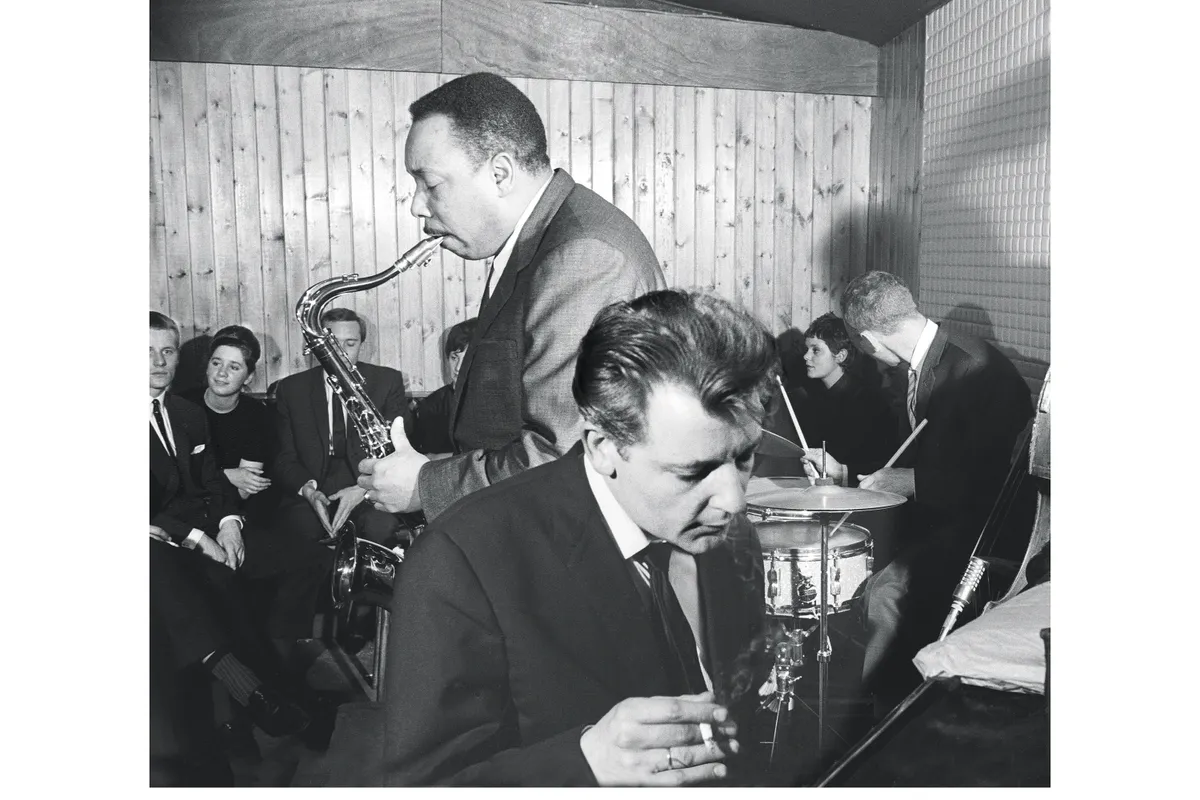

Stan Tracey (b.1926)

Some non-American jazz players resent the music’s Yankee pedigree, feeling it makes them second-class citizens. But the British pianist Stan Tracey is a vibrant example of how anyone can be at home in jazz and forge their own creative voice.

In fact, the Tracey case also shows that jazz can have a life-changing impact even before it’s identified as jazz. Growing up in ordinary, fairly nondescript surroundings in south London in the 1930s, young Tracey happened to hear a record by Andy Kirk’s Kansas City band which at once decided his fate. His subsequent path to a full-time jazz career was circuitous, taking in the accordion, novelty trios and entertaining the troops in World War II. But he played jazz whenever he could and was perfectly content with the kind of wages that come from passing the hat. His burgeoning reputation brought greater financial rewards when he joined Ted Heath’s popular band in 1957, until its adulterated jazz content forced his resignation. However, the ’60s found him immersed in jazz up to his eyeballs: for seven years he was house pianist at Ronnie Scott’s club, playing six long nights a week with Sunday afternoons often thrown in as well. In a way, it was an ideal job.

Tracey impressed such visiting American stars as tenor giant Sonny Rollins, who declared, ‘Does anybody here realise how good he is?’ But the impossible hours and the drugs required to sustain them took their toll, until Tracey’s wife Jackie, fearing for his very survival, made him quit. Since, he has pursued a freelance career, keeping jazz uppermost as performer and composer. His craggy piano style is unmistakeable, a joy of British jazz. His most popular composition remains his suite Under Milk Wood, based on Dylan Thomas’s play. Featuring tenorist Bobby Wellins, and a rhythm section, the selections are grooving medium tempos, aside from the title track and many people’s favourite, the haunting ‘Starless and Bible Black’. I’m partial to the closer, a free-swinging uptempo blues called ‘AM Mayhem’, because its spirit reminds me of his response when I asked him what his ultimate ambition was. ‘To play,’ he replied. ‘Just play: an unending quartet tour.’

Fats Waller (1904-1943)

Depending on his mood, Fats Waller could be ‘the cheerful little earful’ or ‘the harmful little armful’. Usually, he was both, winning a huge following in the 1930s and ’40s with his high-spirited, satiric takes on run-of-the-mill popular songs. He transformed his material with a sense of humour, ebullient vocal style and the infectious swing enshrined in the name of his jumping sextet: Fats Waller and His Rhythm. But jazz fans and musicians prized his glittering piano style. He was a product of the demanding school of New York stride players, whose formidable technique was matched by competitive zest. They challenged each other wherever there was a piano and Waller often prevailed with his sparkling invention and the dexterity, power and finesse you might expect from a sometime pupil of Leopold Godowsky. Waller’s taste for classical music was as natural to him as his genius for swing. He rated JS Bach the third greatest man in history (after Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D Roosevelt) and performed his works on an organ at home. And his own evergreen compositions – such as ‘Honeysuckle Rose’ and ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’’ – exhibit the same kind of refinement as his piano touch. Some of his colleagues believed that his subtler side was frustrated by the non-stop levity that his popular reputation required.

That frustration may have fuelled the heavy drinking which, along with his exhausting routine, led to his death at 39 in 1943. But his many recordings display all the facets of a unique personality, from his demolition of woeful tunes like ‘The Curse of an Aching Heart’ to such famous taglines as ‘One never knows, do one?’, which crowns ‘Your Feet’s Too Big’, to the sheer rampaging abandon of ‘Shortnin’ Bread’. All these gifts from the Waller legacy are included in a selection called Ain’t Misbehavin’, with sterling performances of ‘Blue Turnin’ Grey Over You’ and ‘Jitterbug Waltz’, which features Waller on organ. And gleaming everywhere are the delights of his playing, which set a standard for those he inspired. As the greatest of jazz keyboard virtuosos Art Tatum once put it when asked about his influences, ‘Fats, man, that’s where I come from. Quite a place to come from.’

Jessica Williams (b.1948)

Sometimes you can tell a lot about jazz musicians just from the way they come on stage. When I heard Jessica Williams a few years back, she strolled out supremely relaxed, a rangy blonde with a smile at once confident, welcoming and impish, as if neither she nor we could tell what was going to happen next. Sitting down at the concert grand, she launched into a 15-minute epitome of jazz piano, quarrying themes and spinning out embellishments, alternating cheeky asides and virtuoso flourishes, displaying unlimited imagination and an eye-popping technique that encompassed the whole keyboard. Audiences and musicians have been impressed with what she can do for over 40 years, although Williams, now in her sixties, has pursued her career in her own way. She’s always rejected categories, believing in ‘letting my conservatory training sing through me in a language not jazz, not classical, but mine alone’. But her jazz roots go deep, the result of years of gigging with the biggest names in the business.

Her great distinction is the way she has distilled the whole spectrum of jazz piano into a richly inclusive personal style. She reveres the quirky, splayed, wrong-footing attack of Thelonious Monk, but also the sensitivity of Bill Evans, the harmonies of McCoy Tyner, the prestidigitation of Art Tatum. And she admires Glenn Gould. Given that expressive scope, a Williams solo is always a kind of meditation, an often playful quest to see what secrets a particular tune will yield. And unaccompanied solo playing is her special forte, as revealed on one of her most recent CDs, The Real Deal. Like all her records, it features forays into Monk territory (‘Friday the 13th’, ‘Round Midnight’), plus some surprises, including an impressionistic version of the trad classic ‘Petite Fleur’ which she wryly describes as ‘a wind-up jewellery box’. Some of her best playing is on ballads: ‘Sweet and Lovely’ and ‘My Romance’ embody her spectacular range of abilities – lyricism and deft swing; a darting, striding left hand with glistening runs and arpeggios in the right (or the other way around); Cheshire Cat-lines and chords, and the perpetual impulse of discovery.