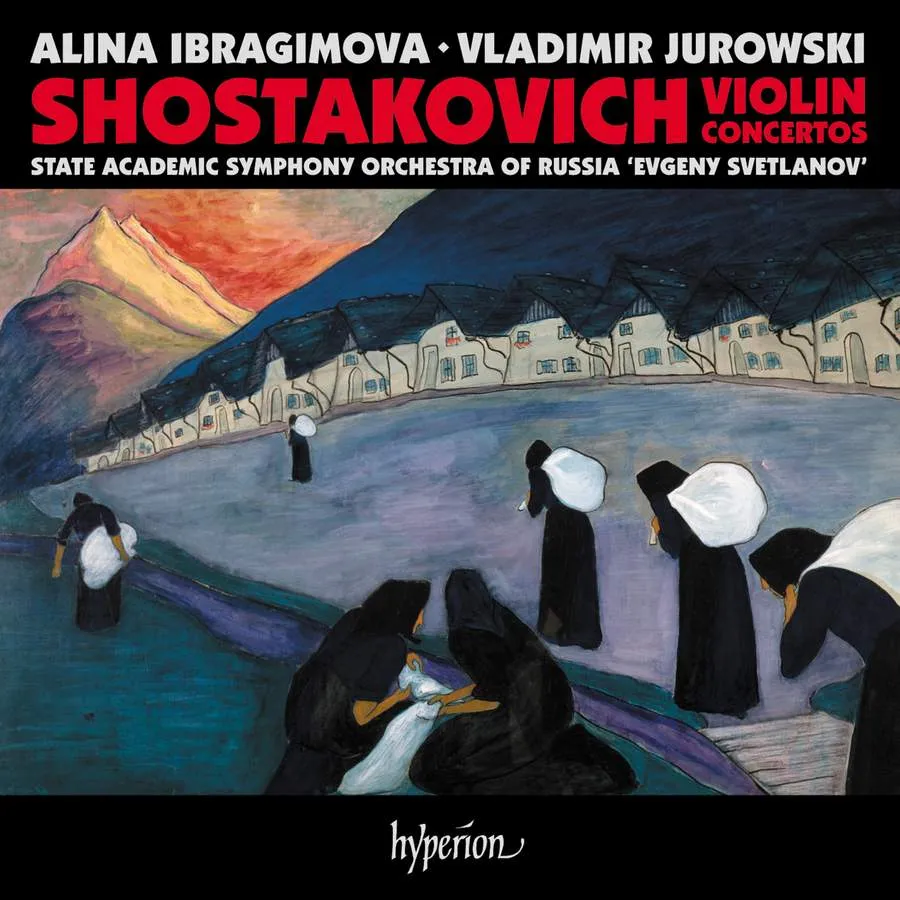

Shostakovich Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 99; Violin Concerto No. 2 in C sharp minor, Op. 129 Alina Ibragimova (violin); State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia 'Evgeny Svetlanov'/Vladimir Jurowski Hyperion CDA68313 71:26 mins

Is the monumental A minor masterpiece here the most recorded violin concerto of recent years? It certainly feels it, perhaps because there have been so many memorable contenders; no violinist sets down an interpretation without having surmounted its incredible technical and emotional challenges. Alina Ibragimova is the latest to make you think you’ve never heard the work better played, and her intense relationship with Vladimir Jurowski and the current incarnation of Yevgeny Svetlanov’s ‘orchestra with a voice’, making just as compelling a case for the sequel concerto, is supernaturally fine-tuned.

By 1967, when he composed the Second Violin Concerto for what he thought was David Oistrakh’s 60th birthday – he was a year premature – Shostakovich could once again speak of pain and suffering more freely, and bring it into even sparer focus. Yet it’s not surprising that he put the First Concerto in a drawer during the dark final years of Stalin’s reign (it was first performed in 1955). In that earlier work, every inflection in the first-movement monologue speaks – this is another take on the Hamlet speech, dedicatee and first performer Oistrakh declared it to be – with a nuance and shaping that can surprise even those who think they know this work well; and the retreat to pp is spellbinding. The dialogues of the great third-movement Passacaglia are as searing as in Oistrakh’s partnerships with conductors Mravinsky and Rozhdestvensky, the fast movements spring and snap; but above all it’s the massive cadenza where Ibragimova goes to the limits, not afraid of making ugly and terrifying sounds.

She also follows recent wisdom on reclaiming the angular opening theme of the finale from xylophone and woodwind; Oistrakh, reasonably, needed a break and Shostakovich granted it in an emendation which has carried over to the printed score. I’ve heard violinists dare to take it back in concert performance; but according to Robert Matthew-Walker, this is the first time it’s featured in a recording (the detail of his long note, incidentally, is very welcome; though I don’t know if anyone still buys into the notion of the Ninth Symphony as a ‘light-hearted work’ – certainly they shouldn’t). Ibragimova keeps it light when she can, so the grim final dance isn’t quite as unrelenting as it can be.

Some correspondences remain with its predecessor in the Second Concerto – the sombre speech of another opening Moderato, for instance. Very much the heart of the piece in this performance, though, is Ibragimova’s constant flow of song and thought in the slow movement, where Shostakovich only allows the soloist a few bars’ rest. Elsewhere sparks fly and there is excellent work from the crucial first horn – albeit not on the same sonic plane as the soloist – and characterful bassoon. The demands on the listener are unrelenting; put a distance between each work so you can come to the sequel fresh for another battering.

David Nice