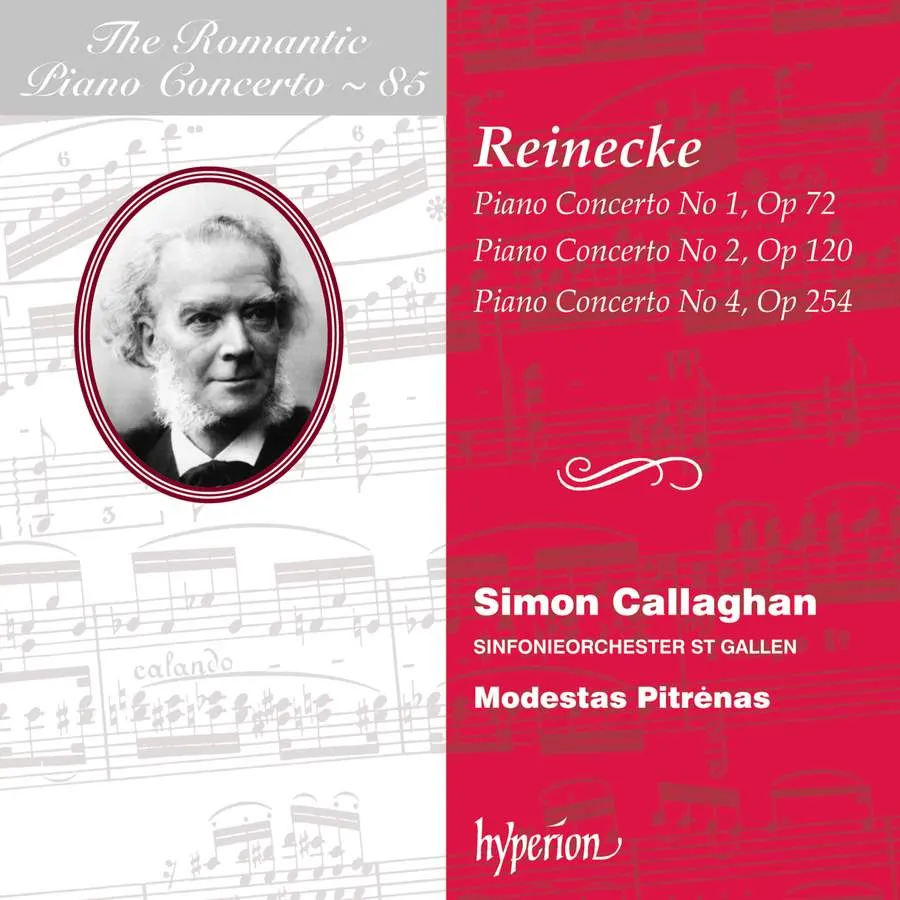

Reinecke Piano Concertos Nos 1, 2 & 4 Simon Callaghan (piano); Sinfonieorchester St Gallen/Modestas Pitrėnas Hyperion CDA68339 76:00 mins

Who’s heard anything by Carl Reinecke? Not me, I have to admit. It’s no wonder Jeremy Nicholas devotes half his liner note to detailing how prolific and influential this pianist, violinist, conductor, arranger, teacher was as a composer, even if his music long ago dropped off the concert-hall map. Born in the year Schubert composed his ‘Death and the Maiden’ Quartet, and dying in the year (1910) Berg wrote his Third Quartet, Reinecke was a big noise on the musical scene for the whole of the Romantic period, and knew all the leading lights; his pupils at the Leipzig Conservatory included Grieg, Sullivan, Stanford, Albéniz and Bruch. And he had quirkier claims to fame: he wrote one of the only two known 19th-century piano sonatas for the left hand alone, and he was the earliest-born musician ever to have made a recording. Though it never figured in a Henry Wood concert, his First Piano Concerto enjoyed great popularity in the late 19th century.

Here we have coruscating performances by Simon Callaghan and the Sinfonieorchester St Gallen of three of Reinecke’s four piano concertos. Written respectively in 1860, 1872 and 1900, they reflect big changes both in their musical hinterland and in his evolving art. The first is imbued with the influence of Mendelssohn in its graceful virtuosity, while the second finds a tone of elegiac grandeur in its Allegro, and a songfulness reminiscent of Tchaikovsky in its Andantino.

The first two movements of the third – coming 28 years later – represent the fruits of maturity. With virtuosity now at the service of a noble structure, its opening Allegro has a Brahmsian authority, while its Adagio has a rapt beauty worthy of Chopin. We should now hear this live.

Michael Church