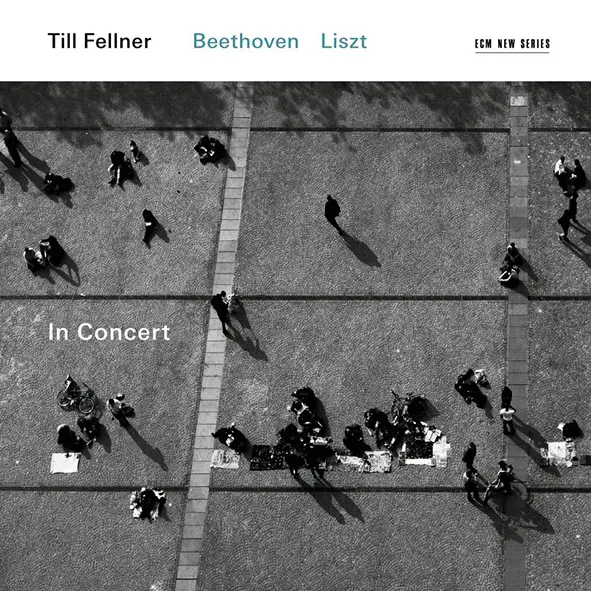

Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111; Liszt Années de pèlerinage; Première année – Suisse Till Fellner (piano) ECM 481 6837 73:58 mins

Till Fellner may be Austria’s top pianist, dominating the field with his Bach and Beethoven while breaking new ground with Larcher and Birtwistle, but he keeps a very low profile: apart from an occasional remark stirring the internet – one comparing Rachmaninov’s music to ‘bad wine’ – he preserves a monastic isolation. He records all his performances, and makes notes on details of articulation and dynamics; he likes to play a programme 10 or 15 times in a row. So we can assume that the live recordings here – the Liszt from 2002 and the Beethoven from 2010 – represent his considered view.

The Liszt is immaculately controlled, each of the nine pieces vividly characterised. His use of pedal is sparing, and his sound is wonderfully clean and precise. His effects are fastidiously calculated: the waters of Lake Wallenstadt lap gently, ‘Orage’ evokes a spiritual upheaval as well as a meteorological one, the bells of Geneva chime with grave jubilation. The emotions stirred up by William Tell’s chapel suggest political solidarity, the delayed resolution of the opening harmonic sequence in ‘Le mal du pays’ conveys an exquisite unease, and the conversation between the baritone and soprano voices of ‘Vallée d’Obermann’ is beautifully delineated. This was a superb recital. The first movement of the Beethoven is disappointing, partly, I suspect, due to a muzzy acoustic. The introduction is sluggish rather than darkly menacing, and there’s no whiff of cordite when the movement gets underway. Yet Fellner amply redeems himself with the finale. He lets the variations develop with a metronomic pulse which at first seems dull, but this is simply to allow the majesty of the movement’s full flowering to surge out; seldom does one hear this visionary music ring with such serene finality.

Michael Church