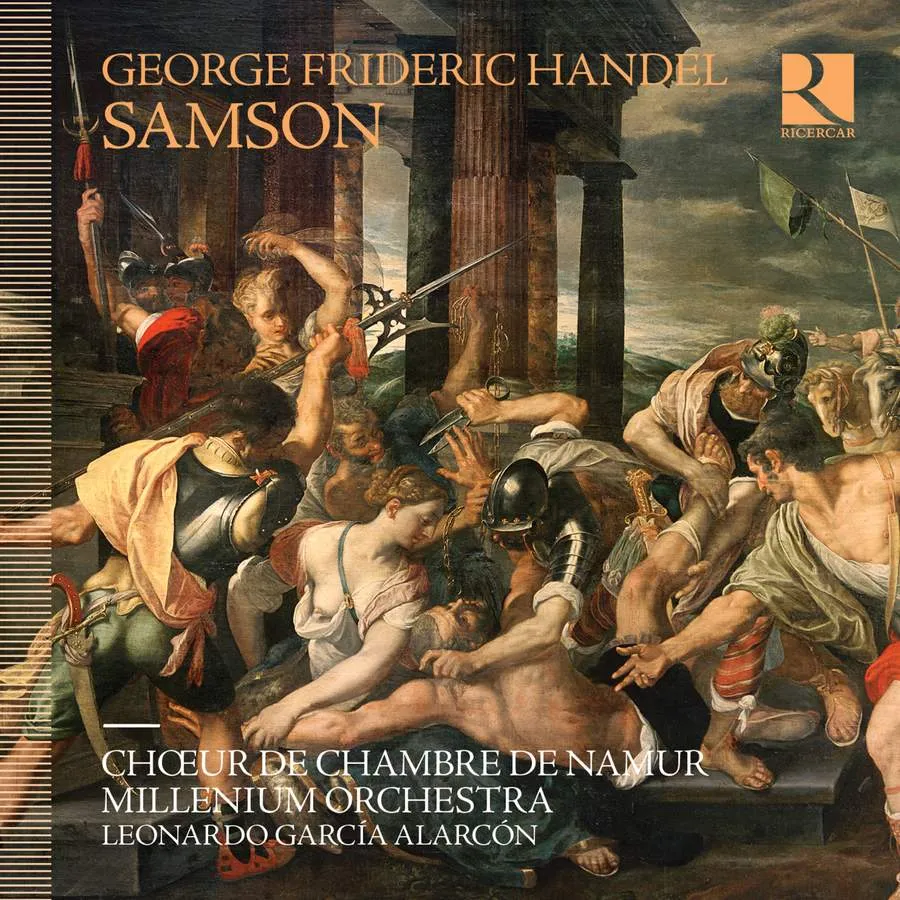

Handel Samson, HWV 57 Matthew Newlin, Maxime Melnik (tenor), Klara Ek, Julie Roset (soprano), Lawrence Zazzo (countertenor), Luigi Di Donato (bass), Chœur de Chambre de Namur; Millennium Orchestra/Leonardo Garcia Alarcon et al Ricercar RIC411 135:29 mins (2 discs)

This live recording of Samson bizarrely follows not Handel’s score, but the mangled, truncated version of the oratorio that Nikolaus Harnoncourt made for his 1994 recording. Why? The sleeve notes tell us that conductor Leonardo García Alarcón regards it as ‘the best’. Yet Harnoncourt’s version scarcely counts as informed practice – among many missteps, Harnoncourt cut Samson’s celebrated aria ‘Why does the God of Israel sleep?’ – and reduces Handel’s three hours and 20 minutes of music to just two and a half hours.

Mounted for a summer festival and the Namur Chamber Choir’s 30th anniversary, this 2018 Samson does give us a period band and several international stars with an Early Music background. German tenor Matthew Newlin, in the title role, delivers more gut-wrenching moments than do most rival Samsons, and Swedish soprano Klara Ek, as the scheming Dalila, can shift chillingly from the coyly sensual to the coldly impersonal. Their shared scenes crackle as they build to the fury-filled duet ‘Traitor to Love’. American-born countertenor Lawrence Zazzo daringly slows his arioso passages to cloak the wise counsellor Micah in simple dignity, while young, fresh-voiced French soprano Julie Roset is strikingly poised as second woman.

To Alarcón’s credit, he’s got interpretative chops: his phrasing is comely, he makes dance-based movements bubble along and he compels the choir to sing its parts in character, whether as Philistines or as Israelites. But he draws little extemporisation from the singers, or the band, or the continuo section, which is an approach as unaccountable as his choice of Harnoncourt’s score over Handel’s.

Berta Joncus