Read on for the story of how the legendary adventurer and feminist icon Amelia Earhart inspired a beautiful, atmospheric new violin concerto.

Amelia Earhart set two world records in 1932 – flying alone across the Atlantic Ocean in 15 hours, becoming the first woman and only the second person in history to do so; and subsequently flying non-stop across the US, again the first time a woman had achieved the feat.

These magnificent records made Earhart an instant worldwide sensation. Independent and adventurous since childhood, she knew on her very first flight in December 1920 with experienced pilot Frank Hawks that her place was in the air. ‘As soon as I left the ground, I knew I myself had to fly,’ she revealed.

What happened to Amelia Earhart?

Her final adventure in a Lockheed 10-E Electra, purchased for her by benefactors of Purdue University where she served as a visiting aviation professor, might easily have become her greatest record yet – to be the first woman to complete a circumnavigational flight of the globe. But in a disastrous turn of events, Earhart and her navigator Fred Noonan never completed the trip, failing to locate their refuelling stop of Howland Island, a tiny, two-mile strip of land in the Pacific Ocean, on 2 July 1937.

Neither the plane nor its crew were found during an exhaustive search of air and sea. And, despite numerous outlandish theories surrounding the incident, it is presumed the two ran out of fuel and ditched into the Pacific.

It should come as little surprise that the intrepid Earhart has inspired a slew of articles and books, documentaries and films, songs and theatre productions. She was even immortalised in plastic as one of a new line of Barbie dolls introduced in 2018, depicting inspirational women. Yet the classical music world has failed to embrace her story – until now.

What work is inspired by Amelia Earhart?

Enter composer Michael Daugherty, whose violin concerto Blue Electra, based on the life of Amelia Earhart, received its world premiere in November 2022. That took place at Washington’s Kennedy Center, just a stone’s throw from Earhart's famous Vega 5B.

Commissioned by violinist Anne Akiko Meyers, who performed the work over three consecutive nights with the National Symphony Orchestra under Gianandrea Noseda, the concerto is a vivid and often beautiful tribute to its subject.

What are the four movements of Blue Electra called?

Its four movements each depict a different period in Earhart’s life. The opening section, ‘Courage (1928)’, is a musical reflection on a poem written by Earhart before her first flight across the Atlantic. Not only did this amazing woman set aviation records, she also wrote three books and numerous verses. These were eventually donated to Purdue University by her granddaughter. Daugherty responds to the poem with a soaring, tuneful opening, encapsulating ideas of heroism, ambition and the sensation of gliding thrillingly above the mundane.

The second movement, ‘Paris (1932)’, shifts gear entirely, depicting an imagined high society ‘Hot Jazz’ soirée in which Earhart, having just received the Legion of Honour from the French Government, is guest of honour. Certainly the most fun and upbeat of the concerto’s movements, this slice of jazzy, bluesy nostalgia gives both soloist and orchestra the chance to shine in complicated rhythmic duets and finger- clicking syncopations.

'A shattering silence'

In the third movement, ‘From an Airplane (1921)’, Daugherty moves back in time via a ‘musical rumination’ on another poem written by a much younger Earhart, ‘dreaming of the day she will be in the pilot seat of an airplane as it spirals through the clouds’. Here the music is meditative and atmospheric, emphasised by ghostly harmonics in the violin part and augmented chords in the orchestra.

And finally comes the work’s devastating conclusion, ‘Last Flight (1937)’, a frighteningly programmatic depiction of Earhart’s disastrous attempt to cross the Pacific Ocean in her Lockheed Electra, its rhythms shot through with the unmistakable SOS Morse code signal and climaxing with a repeated open string G in the solo violin part, taken up gradually by the entire orchestra and crescendoing to a wall of ear-splitting sound, before cutting off abruptly in a shattering silence.

How literal is Daugherty's depiction of Amelia Eahart's disappearance in the music?

What does Daugherty imagine is happening at this point? Is this a musical depiction of the propellor stuttering and dying before the plane falls silently from the sky, or perhaps the plane has already hit the water earlier in the movement – in a series of downward swoops heard throughout the orchestra – before Earhart’s last desperate signalling attempts are lost as she sinks beneath the waves?

Daugherty is unsurprisingly non-committal when I catch up with him after the premiere. ‘Yes, one could interpret this as the plane crashing and then going silent,’ he tells me coyly. And indeed, given the mystery surrounding Earhart’s final hours, perhaps a degree of personal interpretation is best.

Meyers also likes the idea of ‘leaving it up to the imagination of the audience’. But she does elaborate: ‘For me, Amelia has crashed, and the water is coming up. It’s incredibly haunting. I asked Michael where that idea had come from for those last bars and he said he’d never written anything like it before, but that it just presented itself to him.’

Why Amelia Earhart?

It was Daugherty’s body of previous works that initially drew Meyers to him, particularly his 2015 cello concerto Tales of Hemingway and his Fire and Blood of 2003 for solo violin and orchestra, inspired by artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. ‘I love that Michael always uses a very interesting personality or story to create his scores,’ she explains. ‘But when I commissioned the concerto, I had no idea he would pick Amelia Earhart as his subject.

'He composed the work during the pandemic and when he sent me the score, it was perfection. I’d never really thought about Earhart before, but I’ve since become enamoured with her personality and brave soul. You can’t help but think of what she went through in her very short time on earth. To fly as a female at that time in history in those tiny planes – she was the epitome of courage.’

Musical works inspired by icons

For his part, Daugherty has ‘always admired Earhart’s story and life’ and explored the archives at Purdue University, where most of her papers and photographs are located, in preparation for writing the piece. ‘For the last 30 years I’ve composed works inspired by icons such as Rosa Parks, Elvis, Jackie O, Paul Robeson, Stokowski, Georgia O’Keeffe and many others,’ he says. ‘Amelia Earhart fits that aesthetic – and in many ways Blue Electra is a synthesis of what I have been exploring musically over the last decades.’

The symbolism of Earhart as the adventurous woman, standing apart from the crowd, has neat parallels in the role of violin soloist, spotlit and front of stage – something that is lost on neither Daugherty nor Meyers. ‘The solo violin is always up font in the musical texture of this work,’ he says. ‘It is an instrument capable of projecting many different types of musical expression, from the majestic to the tragic. The violin can soar to great heights like no other instrument.’

‘This work has a lot of deep meaning for me,’ Meyers adds, ‘and I’m always thinking of Amelia while I’m playing it. There are a lot of strange resonances for me as a female violinist in depicting this astonishing female pilot.’

The technical challenges of the music

I wonder whether it’s possible to be thinking of such philosophical parallels while concentrating on what is, at times, a deeply demanding score. ‘To make it all sing is always a challenge,’ Meyers responds. ‘You never want to feel that you’re burdened by the technicalities, but simply to let it flow. And that’s what I want for my audience, too. I don’t want them to think, “That’s really hard!”. I want them to think, “Wow, that was cool” or “That was moving”. A lot of people who have heard this music have said they were in tears at the end.’

And ultimately, in premiering a new and exciting work – particularly one that draws an instant, visceral reaction from its audience – Meyers is channelling a little part of Earhart. The first time those innocent, black markings are translated into sound, the soloist and orchestra become acoustic pioneers. It’s a feeling Meyers knows well, committed, as she has been throughout her career, to extending the violin repertoire in numerous premieres.

This one, though, I sense is special. ‘Stepping on stage for the first rehearsal was such a thrilling experience,’ she enthuses. ‘The brass were magnificent, my cadenza with the marimba player was truly wonderful, and it leapt to life. I was so hungry to hear it – and it didn’t disappoint.’

Find out more about Michael Daughterty's Blue Electra and view the score here.

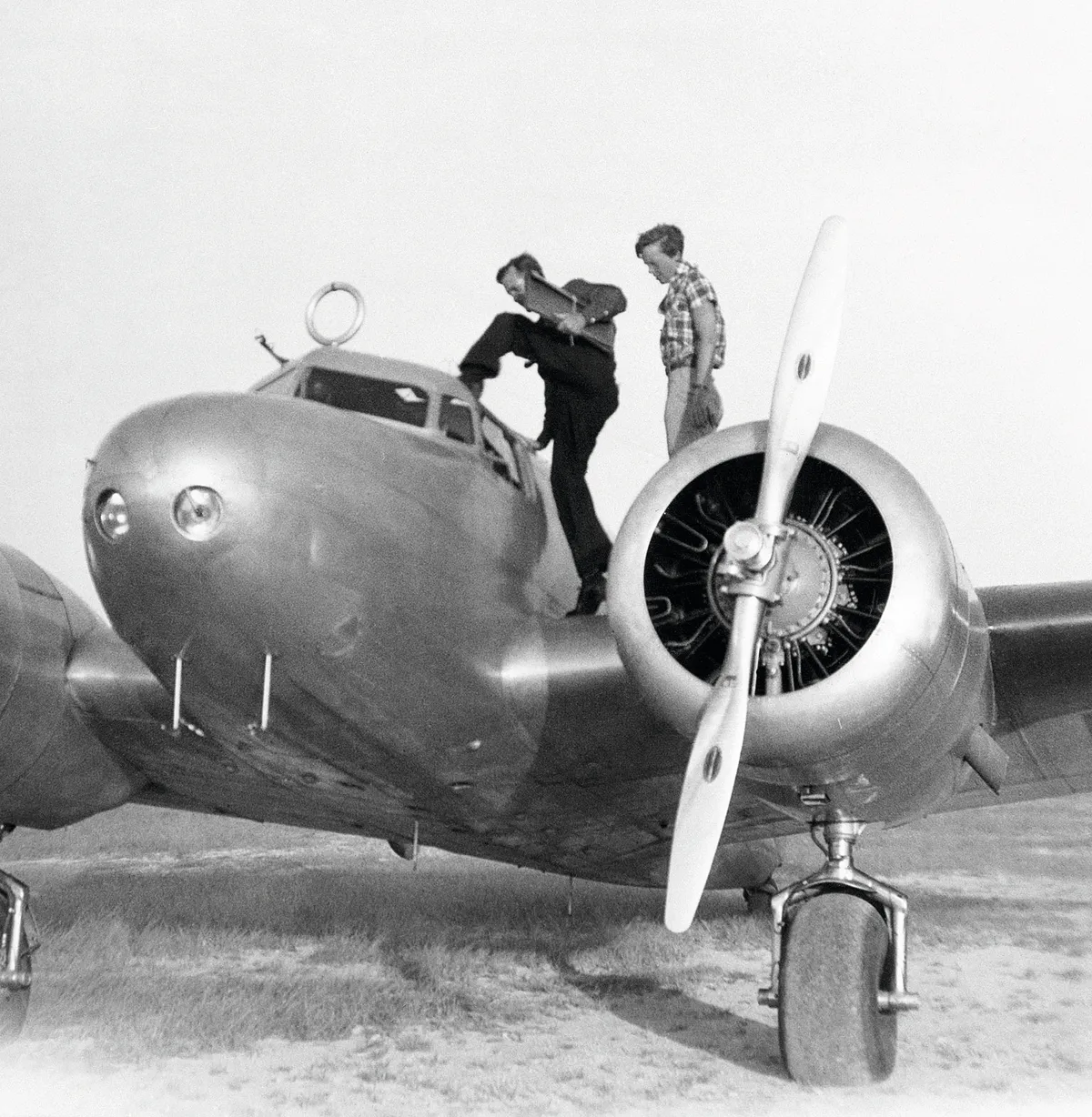

Top image: Amelia Earhart with her bi-plane, Friendship, 1928 (Getty Images)